Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Page 1 of 4

Page 1 of 4 • 1, 2, 3, 4

Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry

- Volume IV - Chapter 55

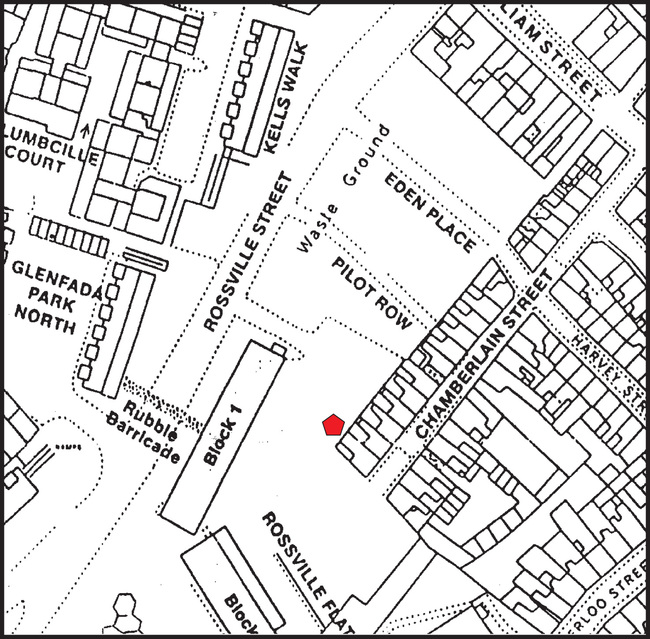

Section: Sector 2: The Launch of the Arrest Operation and Events in the Area of the Rossville Flats

The casualties in Sector 2

Sector 2: The Launch of the Arrest Operation and Events in the Area of the Rossville Flats

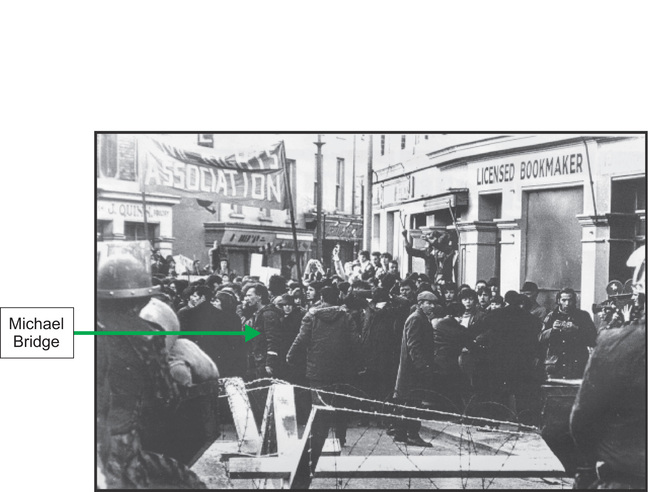

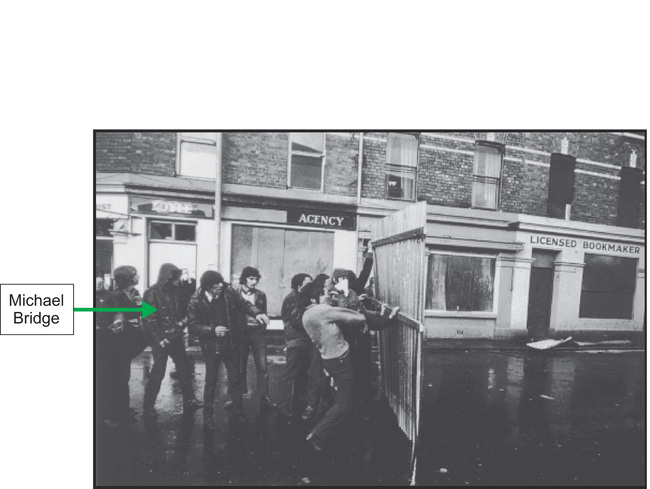

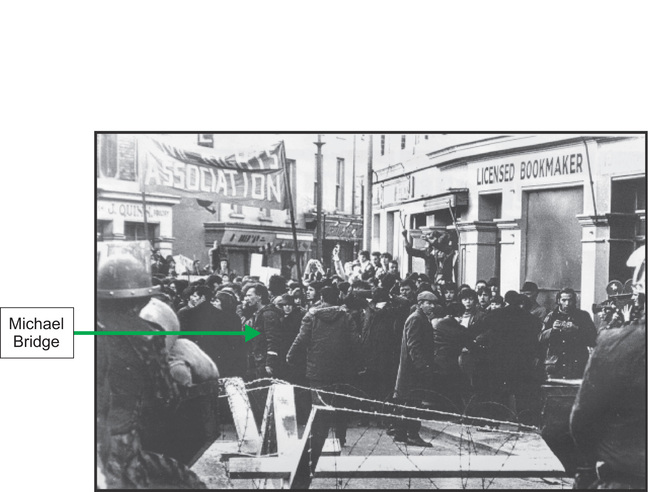

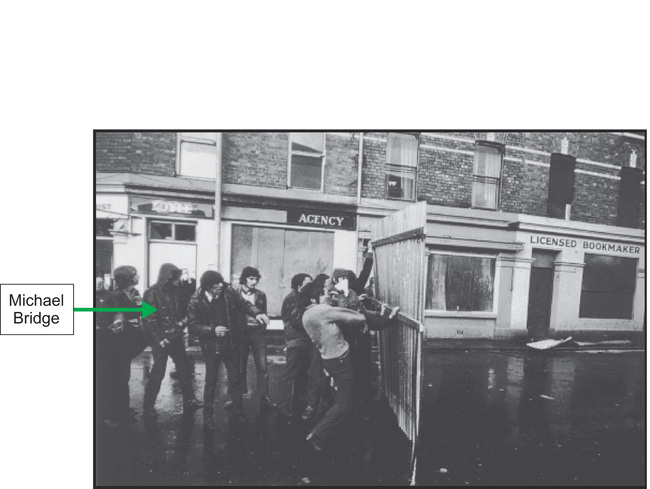

55.1 As we have already indicated, in Sector 2 Jackie Duddy was killed by gunfire, while Margaret Deery, Michael Bridge and Michael Bradley were wounded by the same means. Patrick McDaid, Patrick Brolly and Pius McCarron were also injured, though whether by gunfire or otherwise was a matter of controversy.

Jackie Duddy

55.2 There is no doubt that Jackie Duddy was shot and mortally wounded in Sector 2. There is equally no doubt, and none has been expressed, that he was shot by a soldier.

Biographical details

55.3 Jackie Duddy’s full name was John Francis Duddy. In the course of this Inquiry, witnesses usually referred to him as either Jackie or Jack Duddy. His family knew him as Jackie, and that is the name that we have used in this report.

55.4 Jackie Duddy was 17 years old at the time of Bloody Sunday. He lived in Central Drive, Creggan, with his father, his five brothers, and eight of his nine sisters. His mother had died of leukaemia in 1968, aged 44 years. Jackie Duddy was employed as a weaver in the factory of Thomas French & Sons Ltd on the Springtown Industrial Estate. He was a keen and successful amateur boxer.1

Prior movements

55.5 Jackie Duddy went on the march on Bloody Sunday with some of his friends. His brother Gerry Duddy and sister Kay Duddy recall him saying that he was going to listen to Bernadette Devlin speaking.1

Medical and scientific evidence

55.6 An autopsy of the body of Jackie Duddy was conducted by Dr Derek Carson, then the Deputy State Pathologist for Northern Ireland,1 on 31st January 1972 at Altnagelvin Hospital. Three other doctors and two Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) photographers were also present.2 The notes, reports and photographs from this autopsy have been considered by Dr Richard Shepherd and Mr Kevin O’Callaghan, who were engaged by this Inquiry as independent experts on pathology and ballistics respectively. Dr Carson, Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan, all gave written and oral evidence to this Inquiry. Dr Carson also appeared before the Widgery Inquiry.

55.7 In his autopsy report,1 Dr Carson described the following two gunshot wounds:

1. A fairly neat circular hole, 7mm in diameter, on the outer side of the right shoulder, centred 4cm below the tip of the acromion process. This appeared to be an entrance wound. It was surrounded by a narrow rim of abrasion, 1–2mm wide. There was no appreciable bruising around the wound nor was there any blackening of the skin.

2. A somewhat ragged exit wound, measuring 18mm x 8mm, on the left front. This wound was located near the shoulder and centred 9cm to the left of and 2.5cm above the suprasternal notch, and 14cm above the nipple. The long axis of the wound was almost vertical. It lay within an irregular oval zone of abrasion measuring 32mm x 16mm, around which there was vague reddish-purple bruising within an area measuring 9cm x 4.5cm.

55.8 Dr Carson noted that, with the arm by the side, the two wounds lay in a line passing from right to left, forwards at about 20° to the coronal plane and downwards at about 10° to the horizontal plane. A probe could not be passed through the entrance wound in a direct line between the two, even when the arm was put in a variety of positions.

55.9 The internal injuries found by Dr Carson are described in his report.1

55.10 Dr Carson summarised his conclusions about the fatal injury as follows:1

“Death was due to a gunshot wound of the upper chest. The bullet had entered the outer part of the right shoulder and had passed behind the upper part of the arm bone and the right shoulder blade, notching the inner border of the shoulder blade, before passing through the inner end of the second right rib and the second thoracic vertebra. On striking the spine the bullet had been deflected slightly upwards and had then fractured the middle third of the left collar bone and the adjacent parts of the first and second left ribs before leaving the body through the upper part of the left chest. No bullet was recovered from the body.

In its course through the upper chest the bullet had damaged the upper part of each lung and divided the windpipe, the gullet and the left common carotid and subclavian arteries. Bleeding from the damaged blood vessels and lungs would have caused rapid death, whilst breathing would also have been severely impaired by the injury to the windpipe. Death must have occurred within a few minutes.

The extent of bony injury indicated that the bullet must have been fired from a medium or high velocity weapon but since the missile was not recovered it was not possible to determine the calibre. There was nothing to suggest that the weapon had been discharged at close range.

The track of the wound within the body indicated that after entering the body the bullet had first passed from right to left and slightly downwards until it struck the spine, whence it had been deflected slightly upwards and forwards. If the deceased was fully erect when struck, then the bullet must have come directly from his right and slightly above him. ”

55.11 Dr Carson also described a number of minor external injuries.1 His findings about these injuries were as follows:2

“Superficial injuries on the body surface included a shallow laceration on the outer part of the left eyebrow, and abrasions on the left cheek, the upper lip, the left cheek, the left side of the neck, on the backs of the hands and on the front of the left knee. Some were probably caused when he fell to the ground after being struck by the bullet; others, particularly those on the face and neck with a linear marking, could have been caused by his being dragged along face-downwards, or by his sliding along the ground on falling. All these injuries were of trivial nature and none played any part in the death. ”

55.12 In his oral evidence to the Widgery Inquiry,1 and in his written statement to this Inquiry,2 Dr Carson confirmed the conclusions set out in his autopsy report.

55.13 In their report, Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan reached conclusions similar to those of Dr Carson, which they summarised as follows:1

“[Jackie] DUDDY was struck by a single bullet in the right shoulder which entered the back of the right side of the chest, damaged the right lung, spine, major blood vessels and the left lung and then exited through the left upper chest.

Assuming the Normal Anatomical Position the initial track clearly passed from right to left and there is probably a slight angle backwards. After deflection by the scapula the track passed forwards into the chest where it was again deflected this time by the spine. The greatest care must be exercised in interpreting the track angles in this injury since the mobility of the shoulder may allow for many different positions of the chest and body with the arm in the same position.

The other injuries are minor and due to blunt trauma. The injuries to the face and knee are consistent with a collapse, the injuries to the hand may have been caused in the same way but other forms of minor blunt trauma cannot be excluded. ”

55.14 The photographs of Jackie Duddy’s body taken in the mortuary show the wounds and other injuries described by Dr Carson. We have examined these photographs but do not reproduce them here. A diagram appended to the report of Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan1 illustrates the positions of the wounds.

- Volume IV - Chapter 55

Section: Sector 2: The Launch of the Arrest Operation and Events in the Area of the Rossville Flats

The casualties in Sector 2

Sector 2: The Launch of the Arrest Operation and Events in the Area of the Rossville Flats

55.1 As we have already indicated, in Sector 2 Jackie Duddy was killed by gunfire, while Margaret Deery, Michael Bridge and Michael Bradley were wounded by the same means. Patrick McDaid, Patrick Brolly and Pius McCarron were also injured, though whether by gunfire or otherwise was a matter of controversy.

Jackie Duddy

55.2 There is no doubt that Jackie Duddy was shot and mortally wounded in Sector 2. There is equally no doubt, and none has been expressed, that he was shot by a soldier.

Biographical details

55.3 Jackie Duddy’s full name was John Francis Duddy. In the course of this Inquiry, witnesses usually referred to him as either Jackie or Jack Duddy. His family knew him as Jackie, and that is the name that we have used in this report.

55.4 Jackie Duddy was 17 years old at the time of Bloody Sunday. He lived in Central Drive, Creggan, with his father, his five brothers, and eight of his nine sisters. His mother had died of leukaemia in 1968, aged 44 years. Jackie Duddy was employed as a weaver in the factory of Thomas French & Sons Ltd on the Springtown Industrial Estate. He was a keen and successful amateur boxer.1

Prior movements

55.5 Jackie Duddy went on the march on Bloody Sunday with some of his friends. His brother Gerry Duddy and sister Kay Duddy recall him saying that he was going to listen to Bernadette Devlin speaking.1

Medical and scientific evidence

55.6 An autopsy of the body of Jackie Duddy was conducted by Dr Derek Carson, then the Deputy State Pathologist for Northern Ireland,1 on 31st January 1972 at Altnagelvin Hospital. Three other doctors and two Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) photographers were also present.2 The notes, reports and photographs from this autopsy have been considered by Dr Richard Shepherd and Mr Kevin O’Callaghan, who were engaged by this Inquiry as independent experts on pathology and ballistics respectively. Dr Carson, Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan, all gave written and oral evidence to this Inquiry. Dr Carson also appeared before the Widgery Inquiry.

55.7 In his autopsy report,1 Dr Carson described the following two gunshot wounds:

1. A fairly neat circular hole, 7mm in diameter, on the outer side of the right shoulder, centred 4cm below the tip of the acromion process. This appeared to be an entrance wound. It was surrounded by a narrow rim of abrasion, 1–2mm wide. There was no appreciable bruising around the wound nor was there any blackening of the skin.

2. A somewhat ragged exit wound, measuring 18mm x 8mm, on the left front. This wound was located near the shoulder and centred 9cm to the left of and 2.5cm above the suprasternal notch, and 14cm above the nipple. The long axis of the wound was almost vertical. It lay within an irregular oval zone of abrasion measuring 32mm x 16mm, around which there was vague reddish-purple bruising within an area measuring 9cm x 4.5cm.

55.8 Dr Carson noted that, with the arm by the side, the two wounds lay in a line passing from right to left, forwards at about 20° to the coronal plane and downwards at about 10° to the horizontal plane. A probe could not be passed through the entrance wound in a direct line between the two, even when the arm was put in a variety of positions.

55.9 The internal injuries found by Dr Carson are described in his report.1

55.10 Dr Carson summarised his conclusions about the fatal injury as follows:1

“Death was due to a gunshot wound of the upper chest. The bullet had entered the outer part of the right shoulder and had passed behind the upper part of the arm bone and the right shoulder blade, notching the inner border of the shoulder blade, before passing through the inner end of the second right rib and the second thoracic vertebra. On striking the spine the bullet had been deflected slightly upwards and had then fractured the middle third of the left collar bone and the adjacent parts of the first and second left ribs before leaving the body through the upper part of the left chest. No bullet was recovered from the body.

In its course through the upper chest the bullet had damaged the upper part of each lung and divided the windpipe, the gullet and the left common carotid and subclavian arteries. Bleeding from the damaged blood vessels and lungs would have caused rapid death, whilst breathing would also have been severely impaired by the injury to the windpipe. Death must have occurred within a few minutes.

The extent of bony injury indicated that the bullet must have been fired from a medium or high velocity weapon but since the missile was not recovered it was not possible to determine the calibre. There was nothing to suggest that the weapon had been discharged at close range.

The track of the wound within the body indicated that after entering the body the bullet had first passed from right to left and slightly downwards until it struck the spine, whence it had been deflected slightly upwards and forwards. If the deceased was fully erect when struck, then the bullet must have come directly from his right and slightly above him. ”

55.11 Dr Carson also described a number of minor external injuries.1 His findings about these injuries were as follows:2

“Superficial injuries on the body surface included a shallow laceration on the outer part of the left eyebrow, and abrasions on the left cheek, the upper lip, the left cheek, the left side of the neck, on the backs of the hands and on the front of the left knee. Some were probably caused when he fell to the ground after being struck by the bullet; others, particularly those on the face and neck with a linear marking, could have been caused by his being dragged along face-downwards, or by his sliding along the ground on falling. All these injuries were of trivial nature and none played any part in the death. ”

55.12 In his oral evidence to the Widgery Inquiry,1 and in his written statement to this Inquiry,2 Dr Carson confirmed the conclusions set out in his autopsy report.

55.13 In their report, Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan reached conclusions similar to those of Dr Carson, which they summarised as follows:1

“[Jackie] DUDDY was struck by a single bullet in the right shoulder which entered the back of the right side of the chest, damaged the right lung, spine, major blood vessels and the left lung and then exited through the left upper chest.

Assuming the Normal Anatomical Position the initial track clearly passed from right to left and there is probably a slight angle backwards. After deflection by the scapula the track passed forwards into the chest where it was again deflected this time by the spine. The greatest care must be exercised in interpreting the track angles in this injury since the mobility of the shoulder may allow for many different positions of the chest and body with the arm in the same position.

The other injuries are minor and due to blunt trauma. The injuries to the face and knee are consistent with a collapse, the injuries to the hand may have been caused in the same way but other forms of minor blunt trauma cannot be excluded. ”

55.14 The photographs of Jackie Duddy’s body taken in the mortuary show the wounds and other injuries described by Dr Carson. We have examined these photographs but do not reproduce them here. A diagram appended to the report of Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan1 illustrates the positions of the wounds.

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

55.15 Dr John Martin, then a Principal Scientific Officer in the Department of Industrial and Forensic Science in Belfast, examined the clothing of Jackie Duddy. In his report dated 18th February 19721 he set out the following findings:

“There is a small hole in the right shoulder area of the jacket (item 1). Traces of lead were detected on the edge of this hole which is consistent with a bullet entry. A larger hole in the area of the left chest is consistent with bullet exit. There was corresponding damage to the shirt (item 2). ”

55.16 Dr Martin tested the jacket that Jackie Duddy was wearing when he was shot, and swabs taken from his hands, for the presence of lead particles. Apart from the traces of lead consistent with bullet entry around the hole in the right shoulder of the jacket, Dr Martin detected no significant number of lead particles on the jacket and none on the hand swabs. He concluded that Jackie Duddy had not been using a firearm.1

55.17 Mr Alan Hall, then a Senior Scientific Officer in the same department as Dr Martin, examined the outer clothing of Jackie Duddy for explosives residue. None was detected.1

Where Jackie Duddy was shot

55.18 When discussing the first shots fired by Lieutenant N, we referred to the evidence of the photographer Gilles Peress, who was in Chamberlain Street. After that incident, Gilles Peress ran on to the end of Chamberlain Street.1As he told the Widgery Inquiry, he saw a body in what he described as Rossville Square (by which he meant what we call the car park) beside which was a priest waving a handkerchief.2He then took the following photograph.

“There is a small hole in the right shoulder area of the jacket (item 1). Traces of lead were detected on the edge of this hole which is consistent with a bullet entry. A larger hole in the area of the left chest is consistent with bullet exit. There was corresponding damage to the shirt (item 2). ”

55.16 Dr Martin tested the jacket that Jackie Duddy was wearing when he was shot, and swabs taken from his hands, for the presence of lead particles. Apart from the traces of lead consistent with bullet entry around the hole in the right shoulder of the jacket, Dr Martin detected no significant number of lead particles on the jacket and none on the hand swabs. He concluded that Jackie Duddy had not been using a firearm.1

55.17 Mr Alan Hall, then a Senior Scientific Officer in the same department as Dr Martin, examined the outer clothing of Jackie Duddy for explosives residue. None was detected.1

Where Jackie Duddy was shot

55.18 When discussing the first shots fired by Lieutenant N, we referred to the evidence of the photographer Gilles Peress, who was in Chamberlain Street. After that incident, Gilles Peress ran on to the end of Chamberlain Street.1As he told the Widgery Inquiry, he saw a body in what he described as Rossville Square (by which he meant what we call the car park) beside which was a priest waving a handkerchief.2He then took the following photograph.

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

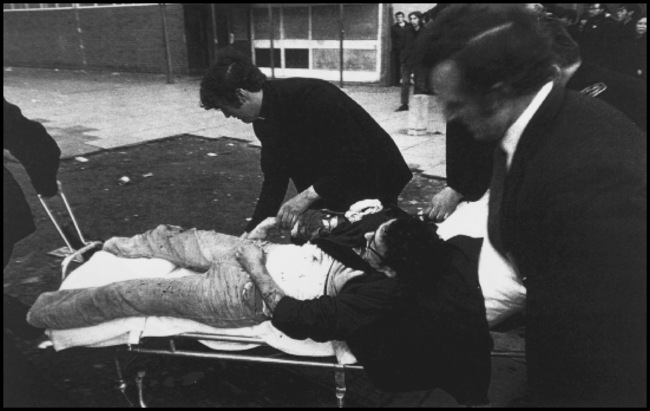

55.19 Fulvio Grimaldi, the photojournalist, told the Widgery Inquiry that he arrived at the south end of Chamberlain Street and saw first aid men and priests around a body in the middle of the car park. He said that he watched them duck as they were being fired at from the direction of the Army vehicles; and that he went back to the corner of Chamberlain Street and shouted at the soldiers to stop firing. The shooting continued; the first three shots went over his head. Fulvio Grimaldi then approached the group around the body and took photographs.1

1 M34.1; WT7.61

55.20 In his evidence to this Inquiry, Fulvio Grimaldi said that his recollection was that shots were fired and he shouted at the soldiers before he saw the body.1He told Paul Mahon2that he had seen Jackie Duddy fall;3Fulvio Grimaldi does not appear to have said this on any other occasion and in our view it is probably wrong. It appears from the Mahon transcript that Fulvio Grimaldi was having difficulty in recalling the sequence of events surrounding the shooting of Jackie Duddy. Fulvio Grimaldi took the following photographs of Jackie Duddy lying in the car park.

1 M34.58; Day 131/31-34

2 Paul Mahon completed an academic dissertation on the events of Bloody Sunday in 1997 and thereafter undertook further substantial research into the subject, in the course of which he conducted a large number of recorded interviews of witnesses, the great majority of whom were civilians.

1 M34.1; WT7.61

55.20 In his evidence to this Inquiry, Fulvio Grimaldi said that his recollection was that shots were fired and he shouted at the soldiers before he saw the body.1He told Paul Mahon2that he had seen Jackie Duddy fall;3Fulvio Grimaldi does not appear to have said this on any other occasion and in our view it is probably wrong. It appears from the Mahon transcript that Fulvio Grimaldi was having difficulty in recalling the sequence of events surrounding the shooting of Jackie Duddy. Fulvio Grimaldi took the following photographs of Jackie Duddy lying in the car park.

1 M34.58; Day 131/31-34

2 Paul Mahon completed an academic dissertation on the events of Bloody Sunday in 1997 and thereafter undertook further substantial research into the subject, in the course of which he conducted a large number of recorded interviews of witnesses, the great majority of whom were civilians.

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

55.21 In his written statement to this Inquiry,1 Liam Bradley identified himself as the man shown wearing a cap in these photographs. In his written statement to this Inquiry, Charles Glenn, a Corporal in the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps, said that the first of these photographs showed the scene as he attended to Jackie Duddy. He can be recognised in this and the other two photographs by his Order of Malta Ambulance Corps uniform.2

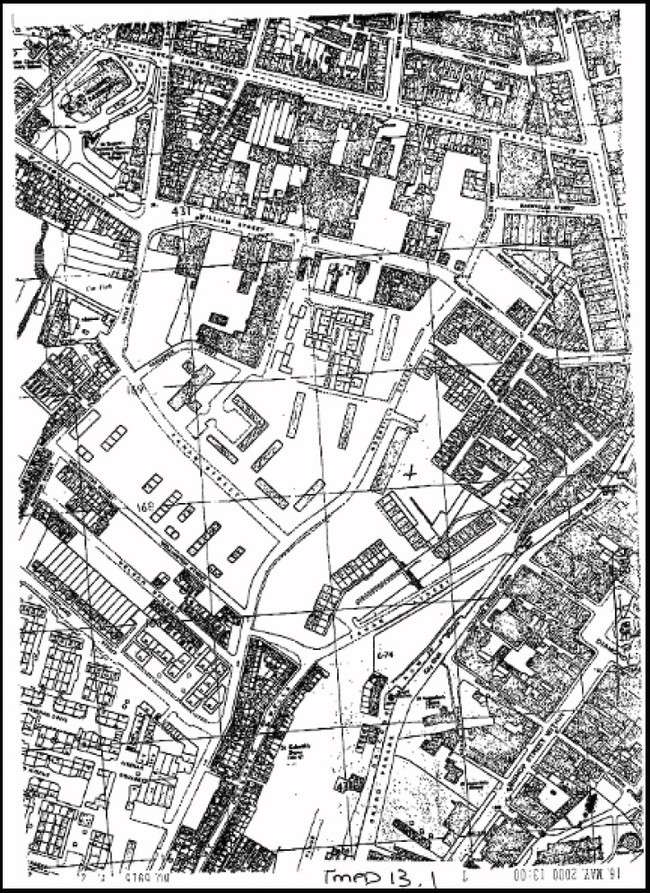

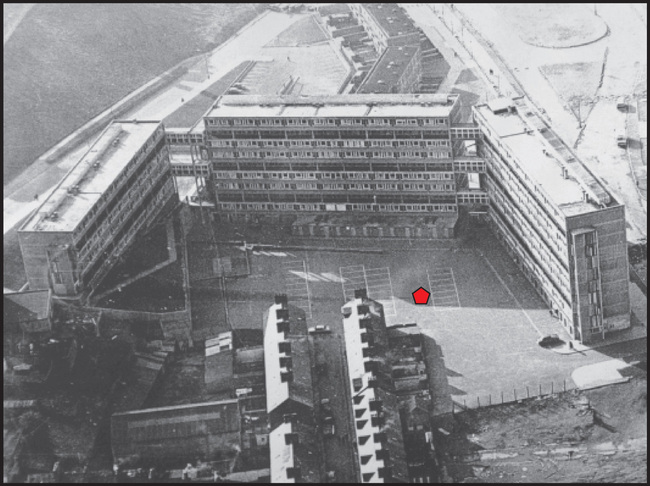

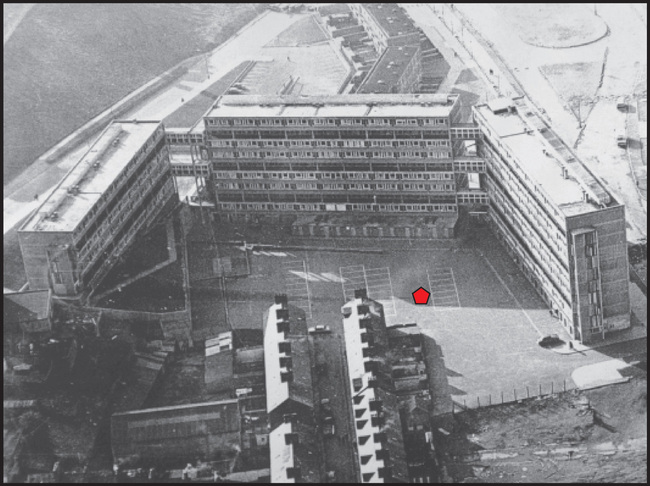

55.22 It is possible, from the lines marking the car park bays, to see more or less exactly where Jackie Duddy was in the Rossville Flats car park when these photographs were taken. However, there is evidence that indicates that he was probably a little further north when he fell.

55.23 Fr Edward Daly (who later became Bishop Daly) is the priest shown in these photographs. In his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry,1 and in an account given to Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times on 16th March 1972,2 he said that he had been in Rossville Street between Eden Place and Pilot Row when he heard the Army vehicles and saw them coming towards Rossville Street. He ran with others across the Eden Place waste ground and past the western end of the wire fence. At about the corner of the Rossville Flats he passed a young boy, and shortly after that, when the boy was a few feet behind him, he heard a shot ring out, looked round, and saw the boy falling. Fr Daly’s evidence was that Jackie Duddy fell forwards onto his face and, alluding to the car park markings, that he “actually fell on the ground on the cross-section of one of those lines – I think about the third or fourth one in. Again I could not swear to that, but it was in the middle of that diagram for the cars ”.3

55.24 Fr Daly ran on, not realising that a live round had hit Jackie Duddy, and then lay on the ground for cover. After a time, he looked over his shoulder and saw Jackie Duddy lying on his back. Fr Daly then went to the aid of Jackie Duddy.1 He did not appreciate that in the meantime a Mr Barber had come to Jackie Duddy’s aid, and until he discovered this Fr Daly was puzzled as to how Jackie Duddy had come to be lying on his back.2

55.25 We are sure that the man to whom Fr Daly referred in his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry was the late Willy Barber, who said in an interview with John Barry of the Sunday Times Insight Team that a young man (evidently Jackie Duddy) had been running on his left and suddenly fell forwards. Willy Barber and someone else put their arms under his shoulders and tried to drag him along, but found him very heavy and turned him over.1

55.26 Brian Johnston told us in his written statement to this Inquiry1 that he saw Jackie Duddy fall forwards onto his face at a point that he indicated on a photograph as being near the centre of the line separating the third and fourth parking bays in the row of seven closest to Block 1 of the Rossville Flats, counting from the end closer to the waste ground.2 Brian Johnston said that after he fell, Jackie Duddy’s head was pointing towards the south-east corner of the car park of the Rossville Flats and his feet were pointing towards Rossville Street.3

55.27 The Inquiry experts Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan noted in their report that Jackie Duddy sustained a number of minor injuries to the face (predominantly on the left side) and the front of the left knee, consistent with a collapse.1 This in turn is consistent with the evidence that Jackie Duddy fell forwards.

55.28 On the evidence of these witnesses we are sure that Jackie Duddy was shot and fell on his face as he was moving in a generally southerly direction, probably somewhere around the centre of the row of seven parking bays closest to Block 1 of the Rossville Flats, and that his body was then dragged a short distance further on and turned over, so as to arrive in the position in which it is seen in the photographs shown above. We set out below an aerial photograph of the Rossville Flats, showing on the basis of this evidence where Jackie Duddy fell and where he was when the photographs were taken.

55.22 It is possible, from the lines marking the car park bays, to see more or less exactly where Jackie Duddy was in the Rossville Flats car park when these photographs were taken. However, there is evidence that indicates that he was probably a little further north when he fell.

55.23 Fr Edward Daly (who later became Bishop Daly) is the priest shown in these photographs. In his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry,1 and in an account given to Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times on 16th March 1972,2 he said that he had been in Rossville Street between Eden Place and Pilot Row when he heard the Army vehicles and saw them coming towards Rossville Street. He ran with others across the Eden Place waste ground and past the western end of the wire fence. At about the corner of the Rossville Flats he passed a young boy, and shortly after that, when the boy was a few feet behind him, he heard a shot ring out, looked round, and saw the boy falling. Fr Daly’s evidence was that Jackie Duddy fell forwards onto his face and, alluding to the car park markings, that he “actually fell on the ground on the cross-section of one of those lines – I think about the third or fourth one in. Again I could not swear to that, but it was in the middle of that diagram for the cars ”.3

55.24 Fr Daly ran on, not realising that a live round had hit Jackie Duddy, and then lay on the ground for cover. After a time, he looked over his shoulder and saw Jackie Duddy lying on his back. Fr Daly then went to the aid of Jackie Duddy.1 He did not appreciate that in the meantime a Mr Barber had come to Jackie Duddy’s aid, and until he discovered this Fr Daly was puzzled as to how Jackie Duddy had come to be lying on his back.2

55.25 We are sure that the man to whom Fr Daly referred in his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry was the late Willy Barber, who said in an interview with John Barry of the Sunday Times Insight Team that a young man (evidently Jackie Duddy) had been running on his left and suddenly fell forwards. Willy Barber and someone else put their arms under his shoulders and tried to drag him along, but found him very heavy and turned him over.1

55.26 Brian Johnston told us in his written statement to this Inquiry1 that he saw Jackie Duddy fall forwards onto his face at a point that he indicated on a photograph as being near the centre of the line separating the third and fourth parking bays in the row of seven closest to Block 1 of the Rossville Flats, counting from the end closer to the waste ground.2 Brian Johnston said that after he fell, Jackie Duddy’s head was pointing towards the south-east corner of the car park of the Rossville Flats and his feet were pointing towards Rossville Street.3

55.27 The Inquiry experts Dr Shepherd and Mr O’Callaghan noted in their report that Jackie Duddy sustained a number of minor injuries to the face (predominantly on the left side) and the front of the left knee, consistent with a collapse.1 This in turn is consistent with the evidence that Jackie Duddy fell forwards.

55.28 On the evidence of these witnesses we are sure that Jackie Duddy was shot and fell on his face as he was moving in a generally southerly direction, probably somewhere around the centre of the row of seven parking bays closest to Block 1 of the Rossville Flats, and that his body was then dragged a short distance further on and turned over, so as to arrive in the position in which it is seen in the photographs shown above. We set out below an aerial photograph of the Rossville Flats, showing on the basis of this evidence where Jackie Duddy fell and where he was when the photographs were taken.

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

55.29 According to the Sunday Times Insight article published on 23rd April 1972,1 Neil McLaughlin, Jackie Duddy and others came along Chamberlain Street from William Street, and seeing the Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) drawn up in the car park surged towards it, “most if not all of them ” on their way to the back of the car park. However, a note prepared by John Barry of the Sunday Times Insight Team of an interview with Neil McLaughlin does not explicitly record that the group going along Chamberlain Street and into the car park included Jackie Duddy, but only that it included Neil McLaughlin “and his mates ”.2

55.30 According to this note, while Neil McLaughlin was a “self-confessed aggro man ”, he described Jackie Duddy as someone who usually went miles to avoid trouble. The note does not record Neil McLaughlin saying that Jackie Duddy was taking part in the riot at Barrier 14, and implies the contrary in the remark “If he wasn’t throwing stones, it was only because he was with Jack Duddy ”, though in his written statement to this Inquiry1 Neil McLaughlin admitted that he himself did throw stones.

55.31 Again according to this note, Neil McLaughlin said that the group of which he was part surged towards the soldiers who were disembarking from their vehicle (evidently Sergeant O’s APC). He saw an Order of Malta Ambulance Corps volunteer fall, not necessarily shot, “by the back wall of the C[hamberlain] St row – in other words the crowd running forward had just about cleared the gable end ”; then Margaret Deery was shot on his right and Neil McLaughlin flung himself to the ground, after which he saw a crowd “up in the car park ” clustered around another body; and then Michael Bridge ran past Neil McLaughlin and was shot.

55.32 To our minds this evidence suggests that Neil McLaughlin’s group was active in the area around the gable end and side wall of the garden of 36 Chamberlain Street, rather than in the area where Jackie Duddy was shot; and that if (as seems to us to be the case) Jackie Duddy was the person around whose body a crowd was clustered in the car park, he must have parted company with Neil McLaughlin some time before he was shot.

55.33 Neil McLaughlin’s evidence to this Inquiry was that he now had no recollection of seeing Jackie Duddy at all on Bloody Sunday, either before or after he was shot, although he accepted that it was possible that he had done so.1 He took issue with, or said that he had no recollection of, several matters recorded in John Barry’s note.2 However, we are of the view that John Barry’s note is likely to be an accurate account of what he was told by Neil McLaughlin.

1 AM347.9; Day 91/15; Day 91/18 2Day 91/16-37

55.34 In his written evidence to this Inquiry,1 Kevin Leonard told us that he recalled seeing Jackie Duddy throwing stones in the group of people rioting with him at Barrier 14, and that Jackie Duddy was ahead of him when they ran down Chamberlain Street. However, in his oral evidence to this Inquiry, he accepted that this was all presumption on his part:2

“Q. It seems to be the case that when you saw a person shot in the courtyard of the flats you did not appreciate that it was Jackie Duddy?

A. No, not at the time.

Q. Is it the case, really, that you presumed that because this person was shot in a group ahead of you running across the courtyard, he must have run from Chamberlain Street?

A. That is correct.

Q. You presumed also, then, that if he was running along Chamberlain Street, as you had, he must have been in William Street near the barrier as you had?

A. Yes.

Q. And therefore you presumed, effectively, that he was at the barrier in the group throwing stones?

A. Yes, that is correct.

Q. Really you cannot be sure that Jackie Duddy was in this group throwing stones at the barrier, is that fair?

A. Yes, that is a fair comment to say. ”

55.35 In his written statement to this Inquiry,1 Patrick McKeever told us that he and his friend Joseph McGrory were in a group of four or five people running from the south end of Chamberlain Street towards the passage between Blocks 1 and 2 of the Rossville Flats. A young man (evidently Jackie Duddy) was running in the group, and fell in front of Patrick McKeever and to his right, clearly fatally injured. Joseph McGrory gave a similar account in his written statement to this Inquiry,2 but added that he did not recall whether the young man had been running as part of a group or on his own; and in oral evidence3 he said that people were scrambling in all directions and he would never have known from where the young man had come.

55.36 There is other evidence that suggests that Jackie Duddy may not have come down Chamberlain Street. We set out below, with some changes and additions, what we regard as an accurate summary of this evidence prepared by Counsel to the Inquiry:1

(a) In his written statement to this Inquiry2 (see also his interview with Jimmy McGovern3,4), Gerry Duddy said that he spoke to his brother Jackie at about the point marked C on the plan attached to his statement5 (on Rossville Street near the north end of Kells Walk). His brother told him that he had been up by the Army barrier in William Street. After a few minutes, his brother said that he was heading off, crossed Rossville Street and started to walk across the waste ground in the direction of the Rossville Flats. Subsequently the Army vehicles entered the area from Little James Street.

(b) In her Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) statement,6 Isabella Duffy described coming out of her brother’s flat in the Rossville Flats and seeing the arrival of the Army vehicles and the disembarkation of the soldiers. She said that she saw a little boy (in our view Jackie Duddy) running across the car park of the Rossville Flats “from the direction of the soldiers ”. She saw the soldiers shooting, and initially thought that they were firing baton rounds, but then saw the boy fall, apparently dead. In her statement to the Widgery Inquiry,7 she said that the boy was running away from the soldiers. In her oral evidence to the Widgery Inquiry, she said that her brother’s flat was on the second floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.8,9 She told the Widgery Inquiry10 that the boy was coming “from the Saracens ”. In her statement to this Inquiry,11 she said that she saw Jackie Duddy running in from the entrance to the car park, and that he seemed to be at the tail end of the people who had run down William Street (sic) towards the Rossville Flats.

(c) In his written statement to this Inquiry,12 Brian Johnston said that Jackie Duddy had run from the waste ground by Pilot Row into the car park of the Rossville Flats, at the tail end of a small group.

3 Jimmy McGovern was the scriptwriter of the Channel 4 drama-documentary Sunday, first broadcast on 28th January 2002 to mark the 30th anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

9 Isabella Duffy gave us a different description of the location of her brother’s flat (AD158.1). However, we are sure that the brother in question was the late Patrick Friel, since Isabella Duffy referred to him as Pat Friel (AD158.1), and Patrick Friel’s son John Patrick Friel told us that Isabella Duffy was his aunt (AF32.25). Patrick Friel’s address was 19 Garvan Place (AF38.1; AF38.3), which was at the western end and on the second and third floors of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.

55.37 It will be seen from the foregoing that there is conflicting evidence as to whether Jackie Duddy had come into the car park from the southern end of Chamberlain Street or from the Eden Place waste ground. On the whole we consider the latter the more likely. In this regard, although Fr Daly told us that he did not know where Jackie Duddy had come from when he saw him,1 his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry was to the effect that he remembered the young boy running beside him: “I was running and he was running and looking back, and I overtook him. He laughed at me. He was amused to see me running. ” There was then this passage:2

“LORD WIDGERY: But you overtook him?

A. Yes. I am not an athlete myself. I do not think I am a very graceful runner. He looked at me at this point about the corner of the wire. That is why he stuck in my memory. I went in here and the Saracens came right up this way, and I remember that the first shot I heard, this young boy was about a few feet behind me and there was a shot, and simultaneously he gasped or grunted – something like that. I looked round and he just fell. ”

55.38 We are sure that Fr Daly had come, as he said, from Rossville Street, somewhere between Eden Place and Pilot Row. The wire to which he referred in this passage was in our view the wire fence across the southern edge of the Eden Place waste ground, which Fr Daly must have passed at its western end. To our minds this account by Fr Daly is another indication that Jackie Duddy had come into the car park from the same general direction, rather than from the end of Chamberlain Street.

When Jackie Duddy was shot

55.39 Fr Daly has consistently stated that the shot that hit Jackie Duddy was the first shot that he heard after the soldiers entered the Bogside.1 As already noted, he did not realise at first that what he had heard was a live round as opposed to a baton round, though he did say to us: “I thought the shot was a bit sharp for that of a rubber bullet gun. ”2 Fr Daly told us that he did not recall hearing any reports of baton rounds before Jackie Duddy was shot. It is also clear from Fr Daly’s evidence that Jackie Duddy was shot soon after the soldiers arrived.3

55.40 Brian Johnston, to whose evidence we have referred earlier in this chapter,1 gave a Keville interview2 in which he described seeing Jackie Duddy fall about four to five feet to his right; and went over to lift him up. He said: “… I know that up until this stage there were no guns fired at all. ”

55.41 We have discussed earlier in this report1 the circumstances of the arrest of William John Doherty by Sergeant O near the back wall of the Chamberlain Street houses, which from the evidence we have considered in that context was soon after Sergeant O’s APC had arrived in the car park. We now describe the evidence of a number of civilian witnesses whose accounts seem to us to show that Jackie Duddy was shot at the same time as, or immediately after, this incident.

55.42 We have referred above1 to John Barry’s note of his interview of Willy Barber. According to this note, Willy Barber said that he ran past a paratrooper who was trying to beat hell out of an old man with the barrel of his rifle. He turned at “the Chamberlain St gable ” and saw someone thumping the soldier in the face. This enabled the old man to run off, but the soldier apprehended him again. Willy Barber ran, and a young man running beside him fell.2 It seems to us that the “old man ” was William John Doherty, and from Willy Barber’s account of then trying to move the fallen man, which we have considered above, we are sure that this was Jackie Duddy.

55.43 We have also referred above1 to the evidence of Isabella Duffy when considering the direction from which Jackie Duddy had come. In her NICRA statement, Isabella Duffy said that after she had seen a boy fall in the car park of the Rossville Flats she saw an old man being beaten.2 In our view she was referring to Jackie Duddy and William John Doherty respectively.

55.44 Elizabeth Dunleavy told us that she saw the shooting of Jackie Duddy after she had seen three soldiers beating a “boy ” (who may well have been William John Doherty) and after a “boy ” in Order of Malta Ambulance Corps uniform had been hit by a baton round (perhaps Charles Glenn, although if so Elizabeth Dunleavy appears to have been mistaken as to how he was hurt).1 Her NICRA statement2 does not refer to the beating, but places the other two incidents in the same sequence.

55.45 We have already referred1 to some of the evidence of Charles Glenn, a Corporal in the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps, when considering the arrest of William John Doherty. As we have already noted, Charles Glenn described how he was hit with a rifle butt and knocked to the ground after trying to intervene in an incident in which a paratrooper had grabbed an old man, which we consider is likely to have been the arrest of William John Doherty. In his NICRA statement he recorded that as he fell, he heard a shot. He was stunned, but when he recovered, he saw a man lying in a pool of blood in the car park with Fr Daly bending over him.2 We have no doubt this was Jackie Duddy. A similar account appears in the record of Charles Glenn’s interview with Philip Jacobson of the Sunday Times,3 and in his written statement to this Inquiry.4

55.46 Celine Brolly described to this Inquiry being in a flat on the second floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.1 According to her NICRA statement,2 she saw a “First Aid boy ” running to the aid of a middle-aged man who was being punched and battered by three soldiers. The first aid boy was thrown on the ground. “He was still lying on the ground and Father Daly called him. ” It seems from this statement that by then Fr Daly had gone to Jackie Duddy. We consider that this “First Aid boy ” was Charles Glenn, who went to the aid of Jackie Duddy and can be seen beside him in the photographs shown earlier in this chapter.3

55.47 According to his NICRA statement1 Patrick McCrudden was visiting a friend at 37 Donagh Place. This was on the top floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats, at about the centre of that block. He gave an account of seeing the “saracens ” come in, and continued:

“The people were fleeing in panic. While one soldier was attacking a middle-aged man, a member of the Order of Malta attempted to intervene. The soldier turned and struck this first aid man (dressed in the usual grey uniform) first with the butt of the rifle on both body and face and kicked him. The Order of Malta man collapsed and disappeared from view behind a wall. The middle aged man was arrested. Others were being beaten up and arrested in the same manner in different parts of the wasteground.

I glanced down into the courtyard and saw a man lying on the ground with dark red stains on his chest. Father Daly seemed to be attending to this man. ”

55.48 In our view what Patrick McCrudden saw was Sergeant O arresting William John Doherty; Charles Glenn, the Corporal in the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps; and then Fr Daly attending Jackie Duddy.

Whether Jackie Duddy had anything in his hands

55.49 A number of witnesses said that Jackie Duddy had nothing in his hands. As to accounts given in 1972, Fr Daly said in his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry that when he reached Jackie Duddy there was nothing in his hands.1 He also told the Widgery Inquiry that when he passed Jackie Duddy before he fell “he was not carrying anything that I saw in his hand ”.2 William McChrystal recorded in his NICRA statement that when he reached Jackie Duddy Fr Daly was kneeling over his body, and added: “When I arrived at the youth’s side there was no evidence of any weapon, gun, nail-bomb, or stone. ”3 Patrick Gerard Doherty recorded in his NICRA statement4 that he saw Jackie Duddy fall, and that “He had nothing in his hands ”.

55.50 In evidence to this Inquiry Cathleen O’Donnell,1 Brian Ward,2 Kevin Leonard3 and Isabella Duffy4 all told us that Jackie Duddy had nothing in his hands. All except the first of these witnesses gave statements in 1972, but none said anything in those statements about whether Jackie Duddy had anything in his hands when he was shot.5

55.51 On the other hand, two witnesses gave evidence to the opposite effect.

55.52 In his Keville interview1 Christy Lavery described seeing a man fall: “we had just got about three quarters the way across the flats when he fell, as he was falling I saw the blood spurting from his chest and I stopped and turned him over the blood was running out of him he had obviously been shot. ” A little later in this interview he was asked whether any of the people he witnessed being shot or beaten were “armed with any stones or any guns or anything else? ”. He replied: “The boy who was shot had a stone in his hand but he had no arms. When he fell his hand was facing up and there was a stone on it. ”

55.53 Christy Lavery gave written and oral evidence to this Inquiry. In his written evidence he told us that Jackie Duddy had a stone in his right hand.1 In his oral evidence he first described the stone as “pretty small about tennis ball size ”, but later as smaller, perhaps the size of a golf ball or large marble.2

55.54 We have already referred to the evidence of Brian Johnston as to where Jackie Duddy fell, and to his account of what he then did.1 In his written evidence to this Inquiry,2 Brian Johnston told us that when he reached Jackie Duddy: “I saw the fellow’s right hand opening. Inside there was a pebble the size of a bead. I remember thinking ‘my God, did you think you were going to take on the might of the British Army with a pebble’ .” He went on to state that he had since thought about it and believed that the pebble must have been scooped up into his hand as he fell. Brian Johnston said nothing about what Jackie Duddy had had in his hand in his interview with Kathleen Keville or in his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry.3

55.55 On the basis of these accounts, we consider that Christy Lavery and Brian Johnston were the first to reach Jackie Duddy after he had fallen. Both gave accounts of seeing a stone in Jackie Duddy’s right hand. If they were right about this, that stone might well have fallen out of his hand as he was dragged a short distance, which would account for the fact that Fr Daly did not see it when he went to the body. Despite the other evidence to which we have referred above, we have concluded that Jackie Duddy probably did have a stone in his right hand when he was shot, though its size is uncertain.

What Jackie Duddy was doing when he was shot

55.56 Fr Daly1 and a substantial number of other witnesses2 described Jackie Duddy as running southwards when he was shot.

55.57 However, in his written evidence to this Inquiry,1 Patrick Gerard Doherty told us that at the time he was shot Jackie Duddy was “standing shouting at the soldiers, he was not running away ”. He also told us that he thought Jackie Duddy then fell on his back. When he gave oral evidence he was asked about this:2

“Q. When you said to us earlier ‘when they moved out of the way, I seen he was lying on his back’, does that mean that the other people that were in the car park surrounding him and between you possibly and him, that your view was somewhat obscured?

A. Yeah.

Q. I am not suggesting that when you – at some stage he was not on his back, he definitely ended up on his back?

A. (inaudible) when I seen him, he was lying on his back. I only presumed that he had fell to the –

Q. But I am suggesting the body of the evidence is when he was shot he fell on to his face, and after some time he was turned onto his back?

A. Most likely is.

Q. Which is not too far away from what you are saying, but I am suggesting that when you eventually got a clear sight of him lying on his back, it was that that led you to the conclusion that he must have been standing facing the soldiers when he was shot; could you be a bit mistaken about that?

A. Might have been, it has been a long time ago. ”

55.58 Patrick Gerard Doherty said nothing in his NICRA statement about what Jackie Duddy was doing when he was shot.1 In view of the large body of evidence to the effect that Jackie Duddy was running, we believe that Patrick Gerard Doherty was mistaken in his recollection on this point, as he acknowledged could be the case after so long. In our view Jackie Duddy was running away from the soldiers when he was shot.

Whether Jackie Duddy was in the middle of a hostile crowd

55.59 The representatives of the majority of represented soldiers referred to the evidence of Neil McLaughlin, to which we have referred above,1 that having come down Chamberlain Street he and about 20 others advanced, throwing stones at the APC.2 In reliance on that evidence they submitted:3

“It is therefore probable that Jack Duddy was accidentally hit at a time when he was among or close to a hostile crowd that was throwing objects at the soldiers, and when a soldier aimed at another person. ”

55.60 We do not accept this submission. Apart from the fact that no soldier (save perhaps Private R) admitted even the possibility that he had hit anyone by accident, and all maintained that the people that they had hit had been engaged in activities that justified them being shot, the submission proceeds upon the assumption that Jackie Duddy had come down Chamberlain Street with Neil McLaughlin and others who had previously been rioting. For reasons we have given,1we are of the view that Jackie Duddy had probably come from the Eden Place waste ground. Furthermore, we accept Fr Daly’s evidence that Jackie Duddy was near him when he was shot and that, in that area of the car park at least, people were only trying to run away.2

55.61 Fr Daly told us that he was towards the rear of the crowd that ran through the car park of the Rossville Flats. He said that quite a number of people had been running close to him and Jackie Duddy.1 He also gave evidence that a number of people had been running in the immediate vicinity of himself and Jackie Duddy at the time of the shooting, although he emphasised that he had not been counting heads; and that there were a substantial number (some 60 to 100) of panic-stricken and frightened people ahead of him trying to escape through the gap between Blocks 1 and 2 of the Rossville Flats.2

55.62 Brian Johnston (to whom we have referred above1) told us in his written statement to this Inquiry2 that Jackie Duddy was running at the tail end of a small group, having become isolated and fallen a little behind. In his oral evidence he said that the group consisted only of Jackie Duddy, the priest (Fr Daly) and two or three others.3

55.63 Other witnesses, namely Angela Copp,1Kevin McDaid2and Martin Tucker,3have also said that there were a few other people, but not very many, close to Jackie Duddy as he ran.

55.64 Although Jackie Duddy probably had a stone in his right hand when he was shot, we do not know whether he was about to throw it when he was shot. The medical evidence is that he was shot in the right shoulder, which indicates that at the moment of shooting his upper body was turned towards the soldiers from whom he was running, but it does not follow that he was about to throw the stone, as opposed to turning to see where the soldiers were.

Where Jackie Duddy was taken

55.65 In his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry,1 Fr Daly recorded that after he reached Jackie Duddy there was more gunfire, and he and Charles Glenn lay down beside Jackie Duddy. Fr Daly then described giving Jackie Duddy the last rites, and seeing the shooting of Michael Bridge while still lying beside Jackie Duddy. Fr Daly said that Willy Barber and another man crawled out sometime after Michael Bridge had been shot, and offered to help to carry Jackie Duddy to a position where he could receive medical aid. They suggested that Fr Daly should go in front, carrying a white handkerchief, and that they would carry Jackie Duddy behind him. Just as they were about to stand up and make a dash to Chamberlain Street, a gunman appeared at the wall of the last house in Chamberlain Street and (in an incident to which we return later in this report2) fired two or three shots at the soldiers. Fr Daly shouted at the gunman to go away, which he did. Fr Daly remained on the ground for a few more moments, and then rose onto his knees and was about to stand up when the Army opened fire again. He and the others with him lay down again for a while.

55.66 In his interview with Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times,1 Fr Daly said that the scene of him and the others rising and then throwing themselves to the ground when firing broke out again was shown on CBS film footage broadcast in the United States.

55.67 However, the surviving CBS footage1 shows only the next stage of events, in which Fr Daly, waving a bloodstained handkerchief, led the way as Willy Barber, Liam Bradley, Charles Glenn and William McChrystal carried Jackie Duddy out of the car park of the Rossville Flats to Chamberlain Street. This sequence also appears to show Fr Daly reacting to the sound of shooting, and in his oral evidence to us2 he confirmed that there was “gunfire coming in, at that stage, again ”. It must be borne in mind that this gunfire, or some or it, may have been that occurring in Sector 3, as we describe when dealing with the events of that sector.

55.68 Fulvio Grimaldi’s photograph also shows the group led by Fr Daly making their way across the car park.

55.30 According to this note, while Neil McLaughlin was a “self-confessed aggro man ”, he described Jackie Duddy as someone who usually went miles to avoid trouble. The note does not record Neil McLaughlin saying that Jackie Duddy was taking part in the riot at Barrier 14, and implies the contrary in the remark “If he wasn’t throwing stones, it was only because he was with Jack Duddy ”, though in his written statement to this Inquiry1 Neil McLaughlin admitted that he himself did throw stones.

55.31 Again according to this note, Neil McLaughlin said that the group of which he was part surged towards the soldiers who were disembarking from their vehicle (evidently Sergeant O’s APC). He saw an Order of Malta Ambulance Corps volunteer fall, not necessarily shot, “by the back wall of the C[hamberlain] St row – in other words the crowd running forward had just about cleared the gable end ”; then Margaret Deery was shot on his right and Neil McLaughlin flung himself to the ground, after which he saw a crowd “up in the car park ” clustered around another body; and then Michael Bridge ran past Neil McLaughlin and was shot.

55.32 To our minds this evidence suggests that Neil McLaughlin’s group was active in the area around the gable end and side wall of the garden of 36 Chamberlain Street, rather than in the area where Jackie Duddy was shot; and that if (as seems to us to be the case) Jackie Duddy was the person around whose body a crowd was clustered in the car park, he must have parted company with Neil McLaughlin some time before he was shot.

55.33 Neil McLaughlin’s evidence to this Inquiry was that he now had no recollection of seeing Jackie Duddy at all on Bloody Sunday, either before or after he was shot, although he accepted that it was possible that he had done so.1 He took issue with, or said that he had no recollection of, several matters recorded in John Barry’s note.2 However, we are of the view that John Barry’s note is likely to be an accurate account of what he was told by Neil McLaughlin.

1 AM347.9; Day 91/15; Day 91/18 2Day 91/16-37

55.34 In his written evidence to this Inquiry,1 Kevin Leonard told us that he recalled seeing Jackie Duddy throwing stones in the group of people rioting with him at Barrier 14, and that Jackie Duddy was ahead of him when they ran down Chamberlain Street. However, in his oral evidence to this Inquiry, he accepted that this was all presumption on his part:2

“Q. It seems to be the case that when you saw a person shot in the courtyard of the flats you did not appreciate that it was Jackie Duddy?

A. No, not at the time.

Q. Is it the case, really, that you presumed that because this person was shot in a group ahead of you running across the courtyard, he must have run from Chamberlain Street?

A. That is correct.

Q. You presumed also, then, that if he was running along Chamberlain Street, as you had, he must have been in William Street near the barrier as you had?

A. Yes.

Q. And therefore you presumed, effectively, that he was at the barrier in the group throwing stones?

A. Yes, that is correct.

Q. Really you cannot be sure that Jackie Duddy was in this group throwing stones at the barrier, is that fair?

A. Yes, that is a fair comment to say. ”

55.35 In his written statement to this Inquiry,1 Patrick McKeever told us that he and his friend Joseph McGrory were in a group of four or five people running from the south end of Chamberlain Street towards the passage between Blocks 1 and 2 of the Rossville Flats. A young man (evidently Jackie Duddy) was running in the group, and fell in front of Patrick McKeever and to his right, clearly fatally injured. Joseph McGrory gave a similar account in his written statement to this Inquiry,2 but added that he did not recall whether the young man had been running as part of a group or on his own; and in oral evidence3 he said that people were scrambling in all directions and he would never have known from where the young man had come.

55.36 There is other evidence that suggests that Jackie Duddy may not have come down Chamberlain Street. We set out below, with some changes and additions, what we regard as an accurate summary of this evidence prepared by Counsel to the Inquiry:1

(a) In his written statement to this Inquiry2 (see also his interview with Jimmy McGovern3,4), Gerry Duddy said that he spoke to his brother Jackie at about the point marked C on the plan attached to his statement5 (on Rossville Street near the north end of Kells Walk). His brother told him that he had been up by the Army barrier in William Street. After a few minutes, his brother said that he was heading off, crossed Rossville Street and started to walk across the waste ground in the direction of the Rossville Flats. Subsequently the Army vehicles entered the area from Little James Street.

(b) In her Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) statement,6 Isabella Duffy described coming out of her brother’s flat in the Rossville Flats and seeing the arrival of the Army vehicles and the disembarkation of the soldiers. She said that she saw a little boy (in our view Jackie Duddy) running across the car park of the Rossville Flats “from the direction of the soldiers ”. She saw the soldiers shooting, and initially thought that they were firing baton rounds, but then saw the boy fall, apparently dead. In her statement to the Widgery Inquiry,7 she said that the boy was running away from the soldiers. In her oral evidence to the Widgery Inquiry, she said that her brother’s flat was on the second floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.8,9 She told the Widgery Inquiry10 that the boy was coming “from the Saracens ”. In her statement to this Inquiry,11 she said that she saw Jackie Duddy running in from the entrance to the car park, and that he seemed to be at the tail end of the people who had run down William Street (sic) towards the Rossville Flats.

(c) In his written statement to this Inquiry,12 Brian Johnston said that Jackie Duddy had run from the waste ground by Pilot Row into the car park of the Rossville Flats, at the tail end of a small group.

3 Jimmy McGovern was the scriptwriter of the Channel 4 drama-documentary Sunday, first broadcast on 28th January 2002 to mark the 30th anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

9 Isabella Duffy gave us a different description of the location of her brother’s flat (AD158.1). However, we are sure that the brother in question was the late Patrick Friel, since Isabella Duffy referred to him as Pat Friel (AD158.1), and Patrick Friel’s son John Patrick Friel told us that Isabella Duffy was his aunt (AF32.25). Patrick Friel’s address was 19 Garvan Place (AF38.1; AF38.3), which was at the western end and on the second and third floors of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.

55.37 It will be seen from the foregoing that there is conflicting evidence as to whether Jackie Duddy had come into the car park from the southern end of Chamberlain Street or from the Eden Place waste ground. On the whole we consider the latter the more likely. In this regard, although Fr Daly told us that he did not know where Jackie Duddy had come from when he saw him,1 his evidence to the Widgery Inquiry was to the effect that he remembered the young boy running beside him: “I was running and he was running and looking back, and I overtook him. He laughed at me. He was amused to see me running. ” There was then this passage:2

“LORD WIDGERY: But you overtook him?

A. Yes. I am not an athlete myself. I do not think I am a very graceful runner. He looked at me at this point about the corner of the wire. That is why he stuck in my memory. I went in here and the Saracens came right up this way, and I remember that the first shot I heard, this young boy was about a few feet behind me and there was a shot, and simultaneously he gasped or grunted – something like that. I looked round and he just fell. ”

55.38 We are sure that Fr Daly had come, as he said, from Rossville Street, somewhere between Eden Place and Pilot Row. The wire to which he referred in this passage was in our view the wire fence across the southern edge of the Eden Place waste ground, which Fr Daly must have passed at its western end. To our minds this account by Fr Daly is another indication that Jackie Duddy had come into the car park from the same general direction, rather than from the end of Chamberlain Street.

When Jackie Duddy was shot

55.39 Fr Daly has consistently stated that the shot that hit Jackie Duddy was the first shot that he heard after the soldiers entered the Bogside.1 As already noted, he did not realise at first that what he had heard was a live round as opposed to a baton round, though he did say to us: “I thought the shot was a bit sharp for that of a rubber bullet gun. ”2 Fr Daly told us that he did not recall hearing any reports of baton rounds before Jackie Duddy was shot. It is also clear from Fr Daly’s evidence that Jackie Duddy was shot soon after the soldiers arrived.3

55.40 Brian Johnston, to whose evidence we have referred earlier in this chapter,1 gave a Keville interview2 in which he described seeing Jackie Duddy fall about four to five feet to his right; and went over to lift him up. He said: “… I know that up until this stage there were no guns fired at all. ”

55.41 We have discussed earlier in this report1 the circumstances of the arrest of William John Doherty by Sergeant O near the back wall of the Chamberlain Street houses, which from the evidence we have considered in that context was soon after Sergeant O’s APC had arrived in the car park. We now describe the evidence of a number of civilian witnesses whose accounts seem to us to show that Jackie Duddy was shot at the same time as, or immediately after, this incident.

55.42 We have referred above1 to John Barry’s note of his interview of Willy Barber. According to this note, Willy Barber said that he ran past a paratrooper who was trying to beat hell out of an old man with the barrel of his rifle. He turned at “the Chamberlain St gable ” and saw someone thumping the soldier in the face. This enabled the old man to run off, but the soldier apprehended him again. Willy Barber ran, and a young man running beside him fell.2 It seems to us that the “old man ” was William John Doherty, and from Willy Barber’s account of then trying to move the fallen man, which we have considered above, we are sure that this was Jackie Duddy.

55.43 We have also referred above1 to the evidence of Isabella Duffy when considering the direction from which Jackie Duddy had come. In her NICRA statement, Isabella Duffy said that after she had seen a boy fall in the car park of the Rossville Flats she saw an old man being beaten.2 In our view she was referring to Jackie Duddy and William John Doherty respectively.

55.44 Elizabeth Dunleavy told us that she saw the shooting of Jackie Duddy after she had seen three soldiers beating a “boy ” (who may well have been William John Doherty) and after a “boy ” in Order of Malta Ambulance Corps uniform had been hit by a baton round (perhaps Charles Glenn, although if so Elizabeth Dunleavy appears to have been mistaken as to how he was hurt).1 Her NICRA statement2 does not refer to the beating, but places the other two incidents in the same sequence.

55.45 We have already referred1 to some of the evidence of Charles Glenn, a Corporal in the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps, when considering the arrest of William John Doherty. As we have already noted, Charles Glenn described how he was hit with a rifle butt and knocked to the ground after trying to intervene in an incident in which a paratrooper had grabbed an old man, which we consider is likely to have been the arrest of William John Doherty. In his NICRA statement he recorded that as he fell, he heard a shot. He was stunned, but when he recovered, he saw a man lying in a pool of blood in the car park with Fr Daly bending over him.2 We have no doubt this was Jackie Duddy. A similar account appears in the record of Charles Glenn’s interview with Philip Jacobson of the Sunday Times,3 and in his written statement to this Inquiry.4

55.46 Celine Brolly described to this Inquiry being in a flat on the second floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats.1 According to her NICRA statement,2 she saw a “First Aid boy ” running to the aid of a middle-aged man who was being punched and battered by three soldiers. The first aid boy was thrown on the ground. “He was still lying on the ground and Father Daly called him. ” It seems from this statement that by then Fr Daly had gone to Jackie Duddy. We consider that this “First Aid boy ” was Charles Glenn, who went to the aid of Jackie Duddy and can be seen beside him in the photographs shown earlier in this chapter.3

55.47 According to his NICRA statement1 Patrick McCrudden was visiting a friend at 37 Donagh Place. This was on the top floor of Block 2 of the Rossville Flats, at about the centre of that block. He gave an account of seeing the “saracens ” come in, and continued:

“The people were fleeing in panic. While one soldier was attacking a middle-aged man, a member of the Order of Malta attempted to intervene. The soldier turned and struck this first aid man (dressed in the usual grey uniform) first with the butt of the rifle on both body and face and kicked him. The Order of Malta man collapsed and disappeared from view behind a wall. The middle aged man was arrested. Others were being beaten up and arrested in the same manner in different parts of the wasteground.

I glanced down into the courtyard and saw a man lying on the ground with dark red stains on his chest. Father Daly seemed to be attending to this man. ”

55.48 In our view what Patrick McCrudden saw was Sergeant O arresting William John Doherty; Charles Glenn, the Corporal in the Order of Malta Ambulance Corps; and then Fr Daly attending Jackie Duddy.

Whether Jackie Duddy had anything in his hands

55.49 A number of witnesses said that Jackie Duddy had nothing in his hands. As to accounts given in 1972, Fr Daly said in his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry that when he reached Jackie Duddy there was nothing in his hands.1 He also told the Widgery Inquiry that when he passed Jackie Duddy before he fell “he was not carrying anything that I saw in his hand ”.2 William McChrystal recorded in his NICRA statement that when he reached Jackie Duddy Fr Daly was kneeling over his body, and added: “When I arrived at the youth’s side there was no evidence of any weapon, gun, nail-bomb, or stone. ”3 Patrick Gerard Doherty recorded in his NICRA statement4 that he saw Jackie Duddy fall, and that “He had nothing in his hands ”.

55.50 In evidence to this Inquiry Cathleen O’Donnell,1 Brian Ward,2 Kevin Leonard3 and Isabella Duffy4 all told us that Jackie Duddy had nothing in his hands. All except the first of these witnesses gave statements in 1972, but none said anything in those statements about whether Jackie Duddy had anything in his hands when he was shot.5

55.51 On the other hand, two witnesses gave evidence to the opposite effect.

55.52 In his Keville interview1 Christy Lavery described seeing a man fall: “we had just got about three quarters the way across the flats when he fell, as he was falling I saw the blood spurting from his chest and I stopped and turned him over the blood was running out of him he had obviously been shot. ” A little later in this interview he was asked whether any of the people he witnessed being shot or beaten were “armed with any stones or any guns or anything else? ”. He replied: “The boy who was shot had a stone in his hand but he had no arms. When he fell his hand was facing up and there was a stone on it. ”

55.53 Christy Lavery gave written and oral evidence to this Inquiry. In his written evidence he told us that Jackie Duddy had a stone in his right hand.1 In his oral evidence he first described the stone as “pretty small about tennis ball size ”, but later as smaller, perhaps the size of a golf ball or large marble.2

55.54 We have already referred to the evidence of Brian Johnston as to where Jackie Duddy fell, and to his account of what he then did.1 In his written evidence to this Inquiry,2 Brian Johnston told us that when he reached Jackie Duddy: “I saw the fellow’s right hand opening. Inside there was a pebble the size of a bead. I remember thinking ‘my God, did you think you were going to take on the might of the British Army with a pebble’ .” He went on to state that he had since thought about it and believed that the pebble must have been scooped up into his hand as he fell. Brian Johnston said nothing about what Jackie Duddy had had in his hand in his interview with Kathleen Keville or in his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry.3

55.55 On the basis of these accounts, we consider that Christy Lavery and Brian Johnston were the first to reach Jackie Duddy after he had fallen. Both gave accounts of seeing a stone in Jackie Duddy’s right hand. If they were right about this, that stone might well have fallen out of his hand as he was dragged a short distance, which would account for the fact that Fr Daly did not see it when he went to the body. Despite the other evidence to which we have referred above, we have concluded that Jackie Duddy probably did have a stone in his right hand when he was shot, though its size is uncertain.

What Jackie Duddy was doing when he was shot

55.56 Fr Daly1 and a substantial number of other witnesses2 described Jackie Duddy as running southwards when he was shot.

55.57 However, in his written evidence to this Inquiry,1 Patrick Gerard Doherty told us that at the time he was shot Jackie Duddy was “standing shouting at the soldiers, he was not running away ”. He also told us that he thought Jackie Duddy then fell on his back. When he gave oral evidence he was asked about this:2

“Q. When you said to us earlier ‘when they moved out of the way, I seen he was lying on his back’, does that mean that the other people that were in the car park surrounding him and between you possibly and him, that your view was somewhat obscured?

A. Yeah.

Q. I am not suggesting that when you – at some stage he was not on his back, he definitely ended up on his back?

A. (inaudible) when I seen him, he was lying on his back. I only presumed that he had fell to the –

Q. But I am suggesting the body of the evidence is when he was shot he fell on to his face, and after some time he was turned onto his back?

A. Most likely is.

Q. Which is not too far away from what you are saying, but I am suggesting that when you eventually got a clear sight of him lying on his back, it was that that led you to the conclusion that he must have been standing facing the soldiers when he was shot; could you be a bit mistaken about that?

A. Might have been, it has been a long time ago. ”

55.58 Patrick Gerard Doherty said nothing in his NICRA statement about what Jackie Duddy was doing when he was shot.1 In view of the large body of evidence to the effect that Jackie Duddy was running, we believe that Patrick Gerard Doherty was mistaken in his recollection on this point, as he acknowledged could be the case after so long. In our view Jackie Duddy was running away from the soldiers when he was shot.

Whether Jackie Duddy was in the middle of a hostile crowd

55.59 The representatives of the majority of represented soldiers referred to the evidence of Neil McLaughlin, to which we have referred above,1 that having come down Chamberlain Street he and about 20 others advanced, throwing stones at the APC.2 In reliance on that evidence they submitted:3

“It is therefore probable that Jack Duddy was accidentally hit at a time when he was among or close to a hostile crowd that was throwing objects at the soldiers, and when a soldier aimed at another person. ”

55.60 We do not accept this submission. Apart from the fact that no soldier (save perhaps Private R) admitted even the possibility that he had hit anyone by accident, and all maintained that the people that they had hit had been engaged in activities that justified them being shot, the submission proceeds upon the assumption that Jackie Duddy had come down Chamberlain Street with Neil McLaughlin and others who had previously been rioting. For reasons we have given,1we are of the view that Jackie Duddy had probably come from the Eden Place waste ground. Furthermore, we accept Fr Daly’s evidence that Jackie Duddy was near him when he was shot and that, in that area of the car park at least, people were only trying to run away.2

55.61 Fr Daly told us that he was towards the rear of the crowd that ran through the car park of the Rossville Flats. He said that quite a number of people had been running close to him and Jackie Duddy.1 He also gave evidence that a number of people had been running in the immediate vicinity of himself and Jackie Duddy at the time of the shooting, although he emphasised that he had not been counting heads; and that there were a substantial number (some 60 to 100) of panic-stricken and frightened people ahead of him trying to escape through the gap between Blocks 1 and 2 of the Rossville Flats.2

55.62 Brian Johnston (to whom we have referred above1) told us in his written statement to this Inquiry2 that Jackie Duddy was running at the tail end of a small group, having become isolated and fallen a little behind. In his oral evidence he said that the group consisted only of Jackie Duddy, the priest (Fr Daly) and two or three others.3

55.63 Other witnesses, namely Angela Copp,1Kevin McDaid2and Martin Tucker,3have also said that there were a few other people, but not very many, close to Jackie Duddy as he ran.

55.64 Although Jackie Duddy probably had a stone in his right hand when he was shot, we do not know whether he was about to throw it when he was shot. The medical evidence is that he was shot in the right shoulder, which indicates that at the moment of shooting his upper body was turned towards the soldiers from whom he was running, but it does not follow that he was about to throw the stone, as opposed to turning to see where the soldiers were.

Where Jackie Duddy was taken

55.65 In his written statement for the Widgery Inquiry,1 Fr Daly recorded that after he reached Jackie Duddy there was more gunfire, and he and Charles Glenn lay down beside Jackie Duddy. Fr Daly then described giving Jackie Duddy the last rites, and seeing the shooting of Michael Bridge while still lying beside Jackie Duddy. Fr Daly said that Willy Barber and another man crawled out sometime after Michael Bridge had been shot, and offered to help to carry Jackie Duddy to a position where he could receive medical aid. They suggested that Fr Daly should go in front, carrying a white handkerchief, and that they would carry Jackie Duddy behind him. Just as they were about to stand up and make a dash to Chamberlain Street, a gunman appeared at the wall of the last house in Chamberlain Street and (in an incident to which we return later in this report2) fired two or three shots at the soldiers. Fr Daly shouted at the gunman to go away, which he did. Fr Daly remained on the ground for a few more moments, and then rose onto his knees and was about to stand up when the Army opened fire again. He and the others with him lay down again for a while.

55.66 In his interview with Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times,1 Fr Daly said that the scene of him and the others rising and then throwing themselves to the ground when firing broke out again was shown on CBS film footage broadcast in the United States.

55.67 However, the surviving CBS footage1 shows only the next stage of events, in which Fr Daly, waving a bloodstained handkerchief, led the way as Willy Barber, Liam Bradley, Charles Glenn and William McChrystal carried Jackie Duddy out of the car park of the Rossville Flats to Chamberlain Street. This sequence also appears to show Fr Daly reacting to the sound of shooting, and in his oral evidence to us2 he confirmed that there was “gunfire coming in, at that stage, again ”. It must be borne in mind that this gunfire, or some or it, may have been that occurring in Sector 3, as we describe when dealing with the events of that sector.

55.68 Fulvio Grimaldi’s photograph also shows the group led by Fr Daly making their way across the car park.

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 4