Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Page 1 of 4

Page 1 of 4 • 1, 2, 3, 4

Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Volume I

General Introduction

On 29th January 1998 the House of Commons resolved that it was expedient that a tribunal be established for inquiring into a definite matter of urgent public importance, namely “the events on Sunday, 30 January 1972 which led to loss of life in connection with the procession in Londonderry on that day, taking account of any new information relevant to events on that day”. On 2nd February 1998 the House of Lords also passed this resolution. With the exception of the last 12 words, these terms of reference are virtually identical to those for a previous Inquiry held by Lord Widgery (then the Lord Chief Justice) in 1972. Both inquiries were conducted under the provisions of the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921.

In his statement to the House of Commons on 29th January 1998 the Prime Minister (The Rt Hon Tony Blair MP) said that the timescale within which Lord Widgery produced his report meant that he was not able to consider all the evidence that might have been available. He added that since that report much new material had come to light about the events of the day. In those circumstances, he announced:

“We believe that the weight of material now available is such that the events require re-examination. We believe that the only course that will lead to public confidence in the results of any further investigation is to set up a full-scale judicial inquiry into Bloody Sunday.”

The Prime Minister made clear that the Inquiry should be allowed the time necessary to cover thoroughly and completely all the evidence now available. The collection, analysis, hearing and consideration of this evidence (which is voluminous) have necessarily required a substantial period of time.

The Tribunal originally consisted of The Rt Hon the Lord Saville of Newdigate, a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, The Hon William Hoyt OC, formerly the Chief Justice of New Brunswick, Canada, and The Rt Hon Sir Edward Somers, formerly a member of the New Zealand Court of Appeal. Before the Tribunal began hearing oral evidence, Sir Edward Somers retired through ill health. The Hon John Toohey AC, formerly a Justice of the High Court of Australia, took his place. Lord Saville acted throughout as the Chairman of the Inquiry.

The footnotes provide, among other matters, references to the evidence and submissions on which we have based our views and findings. In the electronic version of this report, references are hypertext-linked, so that by clicking on a reference the reader can refer directly to the evidence or submission under consideration. Where photographs are reproduced in the report, we have in most instances considered it unnecessary to give the reference. The referencing system is the same as that used during the course of the Inquiry to identify the particular matter in question from the materials that were collected, considered and published, so that the reader can follow the references contained in that material. The Tribunal is of the view that with few exceptions the evidence and submissions relating to Bloody Sunday that were made publicly available during the course of the Inquiry should continue to be available, so that the report can be read in conjunction with those materials, which to that end form part of this report. The electronic version of the report provides direct access to these materials, which are also available through the Inquiry website.1 Cross-references within the report to other parts of the report are also footnoted and hypertext-linked. Cross-references are to chapters or to paragraphs within chapters. Thus, for example, a cross-reference to paragraphs 75–100 in Chapter 9 appears as paragraphs 9.75–100.

The ranks and titles of witnesses

It should be noted that many of the soldiers who gave evidence to this Inquiry had achieved over the years higher rank than that which they had held in January 1972. A number of civilians (for example, Bishop Daly and Sir Edward Heath) were also known at the time of the Inquiry by different titles from those by which they had been known in 1972. During the course of the Inquiry, all witnesses were addressed by the titles that they held at the time at which they gave their evidence. However, in this report we refer to all such witnesses by the rank that they held or the title by which they were known in January 1972.

For the reasons that we give below, many witnesses were given ciphers in order to preserve their anonymity and that of their families. We have preserved that anonymity in this report.

Legal representatives

In the course of the Inquiry, the families of those who were killed, the surviving casualties, and the families of those injured on Bloody Sunday who have since died were represented by various different combinations of counsel and solicitors. Separate teams of counsel instructed by the Treasury Solicitor appeared on behalf of one large group and three smaller groups of former and serving officers and soldiers, while other military witnesses chose not to be represented. In order to avoid undue complication, we have often referred in this report to submissions made by “representatives of the families” or “representatives of soldiers”, without distinguishing between the different groups, although where necessary we have been more specific. Further details of the families, surviving casualties, military witnesses and other parties represented in the Inquiry, and of their counsel and solicitors, are given in Appendix 1.

Anonymity

With the exception of a number of senior officers who gave evidence under their own names, military witnesses who gave evidence to the Widgery Inquiry were granted anonymity in order to protect them and their families. They gave their evidence under ciphers, which were alphabetical for those who said that they had fired live rounds on Bloody Sunday (the “lettered soldiers”), and numerical for the others (the “numbered soldiers”). Some police witnesses were also granted anonymity for the purposes of the Widgery Inquiry.

At the outset of this Inquiry there was controversy over whether military witnesses, other than those whose identities were already in the public domain, should be granted anonymity. Rulings of the Tribunal that in general they should not, save where special reasons applied, were quashed on judicial review. The Court of Appeal in London held that the Tribunal was obliged to grant anonymity to those who had fired live rounds. The Tribunal considered that the Court’s reasoning applied also to other military witnesses, unless their identities were already clearly in the public domain, and ruled accordingly. Where appropriate, the ciphers used in the Widgery Inquiry were retained, with the addition of the soldier’s rank at the time of Bloody Sunday (for example, Corporal A or Sergeant 001). Military witnesses who had been given no cipher in 1972 were identified by a number preceded by their rank and the letters INQ (for example, Sergeant INQ 1). Military witnesses sometimes referred in their statements to another soldier by an incomplete name, a nickname, or a name that otherwise could not be matched to an individual identifiable from official records. In these cases the Inquiry replaced the name with a numerical cipher preceded by the letters UNK (for example, UNK 1).

Some of the military witnesses in 1972 were given more than one cipher. While this had the potential to cause confusion, this Inquiry had access to unredacted copies of the witness statements and was able to ensure that they were all attributed to the correct witness.

No police officers were granted anonymity in this Inquiry, although some were permitted to give their evidence screened from the view of all but the Tribunal and the lawyers participating in the hearings.

Successful applications for anonymity were also made on behalf of a number of other witnesses, including certain Security Service and Army intelligence officers, whose ciphers were alphabetical (for example, Officer A), and certain witnesses who had formerly been members of the Official or Provisional Irish Republican Army (OIRA or PIRA) or otherwise had connections with the republican movement, whose ciphers consisted of numbers preceded by the letters OIRA, PIRA or RM as appropriate (for example, OIRA 1, PIRA 1 or RM 1).

The Tribunal had access in all cases to the names of the witnesses who gave evidence to this Inquiry.

General Introduction

On 29th January 1998 the House of Commons resolved that it was expedient that a tribunal be established for inquiring into a definite matter of urgent public importance, namely “the events on Sunday, 30 January 1972 which led to loss of life in connection with the procession in Londonderry on that day, taking account of any new information relevant to events on that day”. On 2nd February 1998 the House of Lords also passed this resolution. With the exception of the last 12 words, these terms of reference are virtually identical to those for a previous Inquiry held by Lord Widgery (then the Lord Chief Justice) in 1972. Both inquiries were conducted under the provisions of the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921.

In his statement to the House of Commons on 29th January 1998 the Prime Minister (The Rt Hon Tony Blair MP) said that the timescale within which Lord Widgery produced his report meant that he was not able to consider all the evidence that might have been available. He added that since that report much new material had come to light about the events of the day. In those circumstances, he announced:

“We believe that the weight of material now available is such that the events require re-examination. We believe that the only course that will lead to public confidence in the results of any further investigation is to set up a full-scale judicial inquiry into Bloody Sunday.”

The Prime Minister made clear that the Inquiry should be allowed the time necessary to cover thoroughly and completely all the evidence now available. The collection, analysis, hearing and consideration of this evidence (which is voluminous) have necessarily required a substantial period of time.

The Tribunal originally consisted of The Rt Hon the Lord Saville of Newdigate, a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, The Hon William Hoyt OC, formerly the Chief Justice of New Brunswick, Canada, and The Rt Hon Sir Edward Somers, formerly a member of the New Zealand Court of Appeal. Before the Tribunal began hearing oral evidence, Sir Edward Somers retired through ill health. The Hon John Toohey AC, formerly a Justice of the High Court of Australia, took his place. Lord Saville acted throughout as the Chairman of the Inquiry.

The footnotes provide, among other matters, references to the evidence and submissions on which we have based our views and findings. In the electronic version of this report, references are hypertext-linked, so that by clicking on a reference the reader can refer directly to the evidence or submission under consideration. Where photographs are reproduced in the report, we have in most instances considered it unnecessary to give the reference. The referencing system is the same as that used during the course of the Inquiry to identify the particular matter in question from the materials that were collected, considered and published, so that the reader can follow the references contained in that material. The Tribunal is of the view that with few exceptions the evidence and submissions relating to Bloody Sunday that were made publicly available during the course of the Inquiry should continue to be available, so that the report can be read in conjunction with those materials, which to that end form part of this report. The electronic version of the report provides direct access to these materials, which are also available through the Inquiry website.1 Cross-references within the report to other parts of the report are also footnoted and hypertext-linked. Cross-references are to chapters or to paragraphs within chapters. Thus, for example, a cross-reference to paragraphs 75–100 in Chapter 9 appears as paragraphs 9.75–100.

The ranks and titles of witnesses

It should be noted that many of the soldiers who gave evidence to this Inquiry had achieved over the years higher rank than that which they had held in January 1972. A number of civilians (for example, Bishop Daly and Sir Edward Heath) were also known at the time of the Inquiry by different titles from those by which they had been known in 1972. During the course of the Inquiry, all witnesses were addressed by the titles that they held at the time at which they gave their evidence. However, in this report we refer to all such witnesses by the rank that they held or the title by which they were known in January 1972.

For the reasons that we give below, many witnesses were given ciphers in order to preserve their anonymity and that of their families. We have preserved that anonymity in this report.

Legal representatives

In the course of the Inquiry, the families of those who were killed, the surviving casualties, and the families of those injured on Bloody Sunday who have since died were represented by various different combinations of counsel and solicitors. Separate teams of counsel instructed by the Treasury Solicitor appeared on behalf of one large group and three smaller groups of former and serving officers and soldiers, while other military witnesses chose not to be represented. In order to avoid undue complication, we have often referred in this report to submissions made by “representatives of the families” or “representatives of soldiers”, without distinguishing between the different groups, although where necessary we have been more specific. Further details of the families, surviving casualties, military witnesses and other parties represented in the Inquiry, and of their counsel and solicitors, are given in Appendix 1.

Anonymity

With the exception of a number of senior officers who gave evidence under their own names, military witnesses who gave evidence to the Widgery Inquiry were granted anonymity in order to protect them and their families. They gave their evidence under ciphers, which were alphabetical for those who said that they had fired live rounds on Bloody Sunday (the “lettered soldiers”), and numerical for the others (the “numbered soldiers”). Some police witnesses were also granted anonymity for the purposes of the Widgery Inquiry.

At the outset of this Inquiry there was controversy over whether military witnesses, other than those whose identities were already in the public domain, should be granted anonymity. Rulings of the Tribunal that in general they should not, save where special reasons applied, were quashed on judicial review. The Court of Appeal in London held that the Tribunal was obliged to grant anonymity to those who had fired live rounds. The Tribunal considered that the Court’s reasoning applied also to other military witnesses, unless their identities were already clearly in the public domain, and ruled accordingly. Where appropriate, the ciphers used in the Widgery Inquiry were retained, with the addition of the soldier’s rank at the time of Bloody Sunday (for example, Corporal A or Sergeant 001). Military witnesses who had been given no cipher in 1972 were identified by a number preceded by their rank and the letters INQ (for example, Sergeant INQ 1). Military witnesses sometimes referred in their statements to another soldier by an incomplete name, a nickname, or a name that otherwise could not be matched to an individual identifiable from official records. In these cases the Inquiry replaced the name with a numerical cipher preceded by the letters UNK (for example, UNK 1).

Some of the military witnesses in 1972 were given more than one cipher. While this had the potential to cause confusion, this Inquiry had access to unredacted copies of the witness statements and was able to ensure that they were all attributed to the correct witness.

No police officers were granted anonymity in this Inquiry, although some were permitted to give their evidence screened from the view of all but the Tribunal and the lawyers participating in the hearings.

Successful applications for anonymity were also made on behalf of a number of other witnesses, including certain Security Service and Army intelligence officers, whose ciphers were alphabetical (for example, Officer A), and certain witnesses who had formerly been members of the Official or Provisional Irish Republican Army (OIRA or PIRA) or otherwise had connections with the republican movement, whose ciphers consisted of numbers preceded by the letters OIRA, PIRA or RM as appropriate (for example, OIRA 1, PIRA 1 or RM 1).

The Tribunal had access in all cases to the names of the witnesses who gave evidence to this Inquiry.

Last edited by Antoinette on Tue 22 Jun - 21:48; edited 4 times in total

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Glossary

In this glossary we provide brief explanations of some of the abbreviations and terminology used in the report, or which appear in some of the documents and other evidence to which we refer. Where necessary, in the report itself we provide further details of, in particular, some of the sources of evidence and the issues to which they gave rise. At the end of the glossary we set out a list showing the hierarchy of Army ranks and the abbreviations sometimes used for them. Cross-references within the glossary to other entries in the glossary appear in italics.

Acid bombs

These were bottles filled with acid or another corrosive substance, used as anti-personnel weapons.

Actuality footage

We have used this expression to refer to film footage taken while the events of Bloody Sunday were in progress. The actuality footage available to the Inquiry includes material filmed by two cameramen from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), two from Independent Television News (ITN), one from the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) and one from Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), as well as a film taken from an Army helicopter. There is also a small quantity of actuality footage taken by amateur cameramen, including William McKinney, who was shot dead on Bloody Sunday. Some of the film footage was edited for broadcasting purposes, with the result that the surviving material is not complete and does not necessarily show events in chronological order.

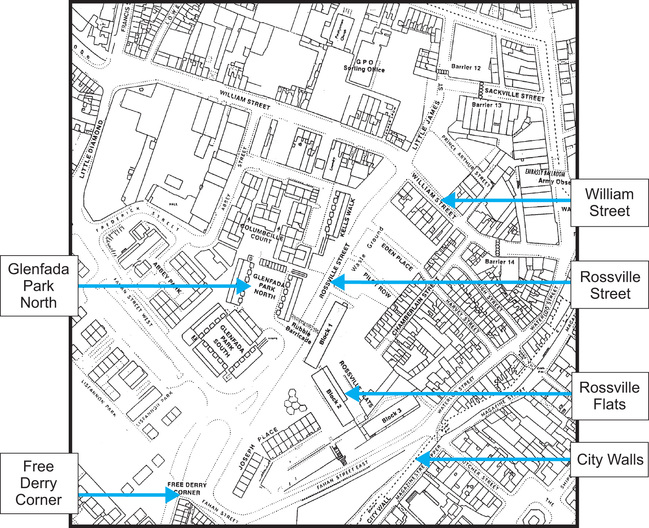

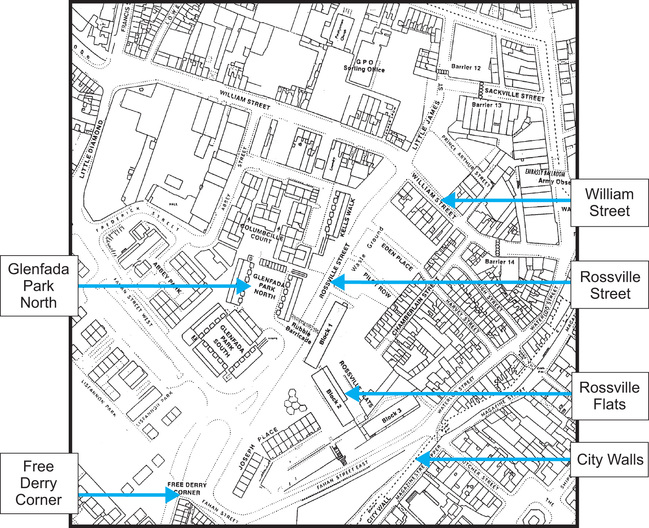

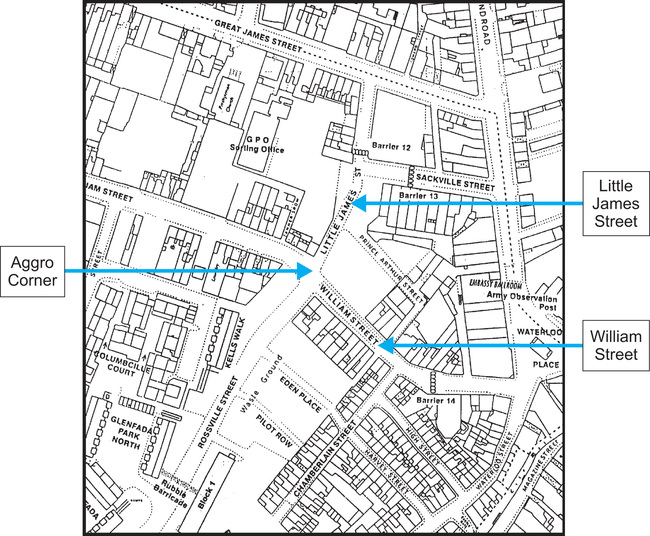

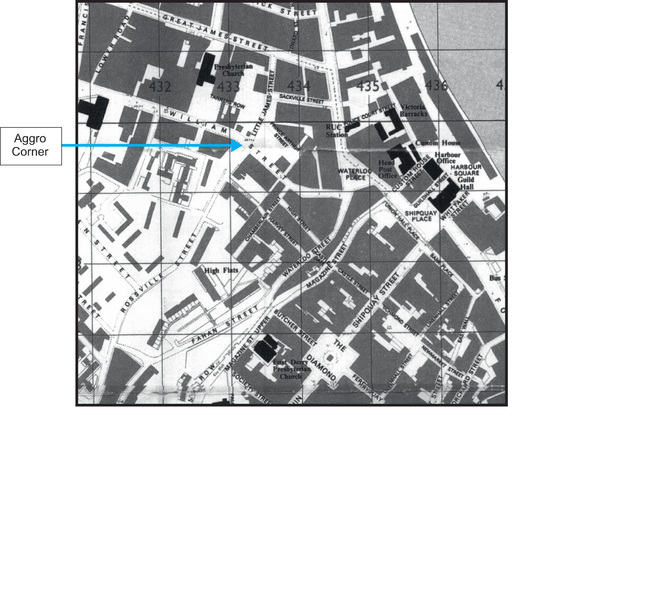

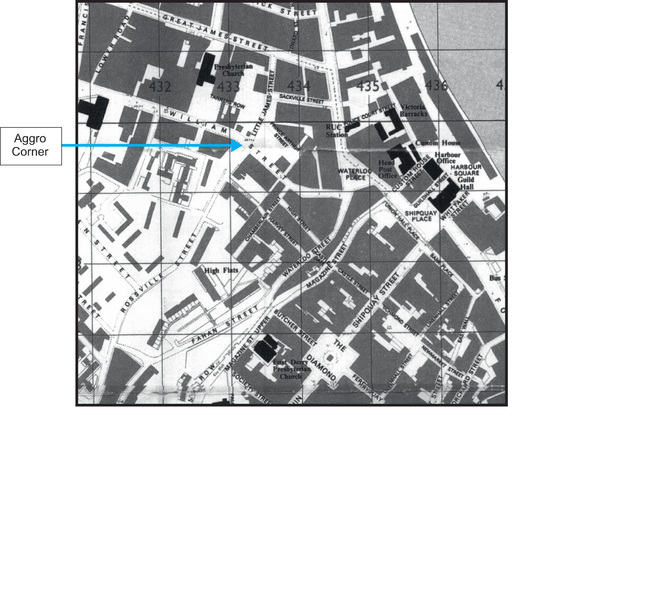

Aggro Corner

This was a slang name, used mainly by the Army, which referred to the junction of William Street, Rossville Street and Little James Street, where trouble had often occurred in the past.

Anti-riot gun

See Baton gun.

APC

Armoured Personnel Carrier. The Humber armoured car was employed routinely as an APC by the Army in Northern Ireland. Several of these vehicles were used on Bloody Sunday. They were often called “Pigs”, mainly by soldiers, either on account of their appearance or because they were awkward to drive and uncomfortable to sit in. They were also frequently described, usually by civilians, as “Saracens”. However, that term was applied inaccurately, since a Saracen was another type of military vehicle, which was not used on Bloody Sunday.

The following photograph, taken by Robert White on Bloody Sunday, shows a Humber APC.

The following photograph, taken from David Barzilay, The British Army in Ulster (Belfast: Century Books, 1978 reprint), shows a Saracen.

Army units

8 Inf Bde

8th Infantry Brigade.

39 Inf Bde

39th Infantry Brigade.

1 CG

1st Battalion, The Coldstream Guards.

1 PARA

1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment.

1 R ANGLIAN

1st Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment.

2 RGJ

2nd Battalion, The Royal Green Jackets.

22 Lt AD Regt

22nd Light Air Defence Regiment, Royal Artillery.

Arrest report forms

When a civilian who had been arrested by a soldier came into the custody of the Royal Military Police (RMP), details of the arrest, including the names of the soldier, the arrested civilian and any witnesses, and the nature of the offence alleged to have been committed, were recorded on what was known as an arrest report form. The form also included space in which to record the date, time and place at which the arrested person was handed over to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and for the RUC to record, where appropriate, the date and time at which the arrested person was charged and whether he or she was kept in custody or released on bail.

Barry interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

Baton gun

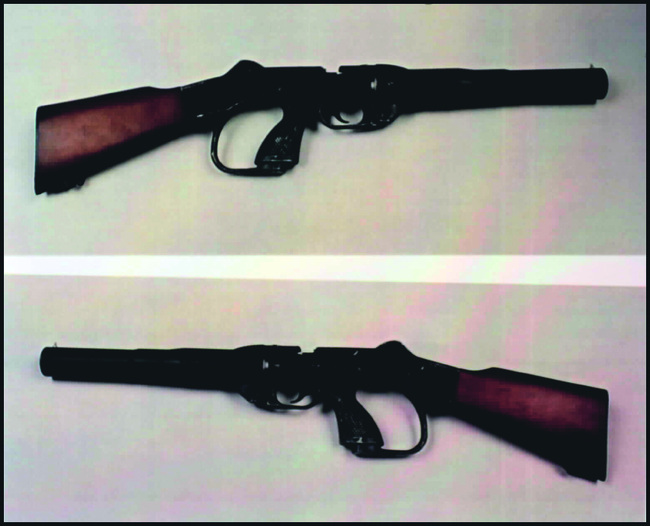

A baton gun was a weapon used to fire baton rounds, otherwise known as rubber bullets, for riot control purposes. On Bloody Sunday many of the soldiers were equipped with baton guns. The baton gun was also known by a variety of other names, including “anti-riot gun”, “RUC gun”, “rubber bullet gun” and “Greener gun”.

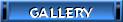

The following photographs show a baton gun.

BID 150

In 1972 the Army in Northern Ireland had access to a secure radio system. Secure communications between a brigade and a battalion under its command could be achieved using an adapted military radio together with a piece of encryption equipment called a BID 150. In this Inquiry the term “BID 150” was often used to refer to the radio and the encryption device together. Whether a BID 150 link was in use between Brigade HQ and the Tactical Headquarters of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday was a matter of dispute, which we consider in the course of the report.

Blast bombs

Blast bombs were improvised devices that consisted of a detonator and explosive material. They were described by some witnesses as being crude anti-personnel devices and like large fireworks or nail bombs but without the nails. We also heard evidence that they could be made with a larger quantity of explosives in order to be used to damage buildings.

Bloody Sunday Inquiry statements

In the course of this Inquiry, written statements were obtained from a large number of witnesses, including civilians, former and serving soldiers, priests, journalists, civil servants, politicians and former members of the IRA. The vast majority of these statements (sometimes called “BSI statements”) were taken by the solicitors Eversheds, who were retained by this Inquiry for this purpose. For this reason some are also sometimes referred to as “Eversheds statements”. The Solicitor to the Inquiry and his assistants also took a number of written statements, and a few were submitted by witnesses or their solicitors.

Brigade HQ

The headquarters of 8th Infantry Brigade, located at Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry.

Brigade net

This was the radio network used to provide communications between Brigade HQ and the headquarters of the battalions and other units under its command. Separate radio networks were used for communications between the headquarters of each battalion and its constituent companies. See also Ulsternet.

Capper tapes

David Capper was a BBC Radio reporter who covered the march on Bloody Sunday. He carried a reel-to-reel tape recorder on which he recorded his commentary on the march. Other voices and sounds are also audible on the recording. The Inquiry obtained a copy of the recording and arranged for a transcript to be made.

CS gas

This is a type of tear gas, which could be fired in grenades or cartridges as a riot control agent.

DIFS

The Department of Industrial and Forensic Science. This department, which formed part of the Ministry of Commerce of the Government of Northern Ireland, was responsible for the forensic tests carried out shortly after Bloody Sunday on hand swabs and clothing obtained from those who had been killed. It was also responsible for matching two bullets, recovered from the bodies of Gerald Donaghey and Michael Kelly, to rifles fired by soldiers on that day.

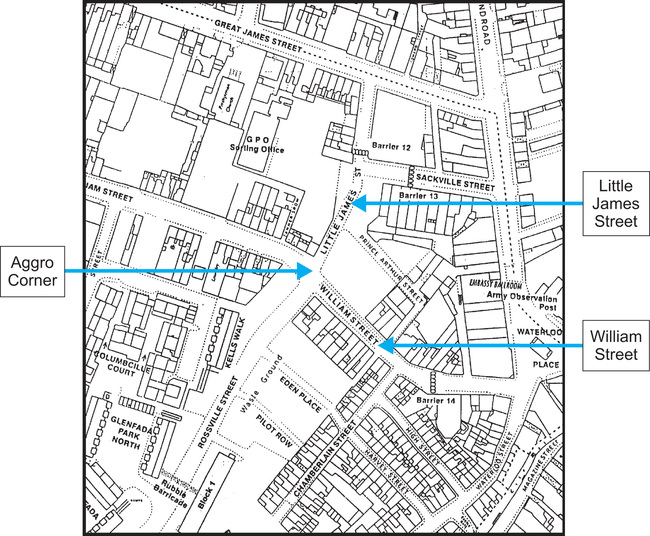

Donagh Place

The seventh, eighth and ninth floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Donagh Place.

Embassy Ballroom

The Embassy Ballroom was located on the west side of Strand Road, close to the northern corner of Waterloo Place. In January 1972 the Army occupied the top floor of the building. Two Observation Posts (OPs) were sited on the roof. OP Echo gave views of William Street, Little James Street, Chamberlain Street, the waste ground north of the Rossville Flats, and the Rossville Flats themselves, including the roofs. OP Foxtrot overlooked Strand Road and Waterloo Place. On Bloody Sunday members of 11 Battery 22 Lt AD Regt manned both these OPs.

Eversheds statements

See Bloody Sunday Inquiry statements.

Ferguson and Thomson interviews

Lena Ferguson and Alexander Thomson were ITN journalists who interviewed a number of former soldiers for the purposes of a Channel 4 News investigation of Bloody Sunday, which resulted in a series of broadcasts transmitted in 1997 and 1998.

Ferret scout car

The Ferret was a lightly armoured scout car which had a two-man crew. On Bloody Sunday, Support Company, 1 PARA used one Ferret scout car, on which a Browning machine gun was mounted. This weapon was not used on Bloody Sunday.

The photograph below, taken by Colman Doyle on Bloody Sunday, shows the Ferret scout car used on that day.

Garvan Place

The first, second and third floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Garvan Place.

Gin Palace

The vehicle in which the tactical headquarters of 1 PARA was located was colloquially known as the Gin Palace.

Greener gun

See Baton gun.

Grimaldi tape

See North tape.

HQNI

Headquarters of the Army in Northern Ireland, located in Lisburn, County Antrim.

Humber armoured car

See APC.

IRA

Irish Republican Army. By 1972 this had split into two separate organisations, the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA. In many cases witnesses and documents referred simply to the IRA, without differentiating between these two organisations.

Jacobson interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

Keville interviews

Kathleen Keville was in Londonderry in January 1972 as a researcher for a film crew making a documentary about Northern Ireland. She had met members of the local civil rights organisation on a previous visit to the city. She took part in the march on 30th January 1972. On the evening of that day and into the next, she recorded the accounts of a number of civilian witnesses on audio tape. Many of these recordings were used to prepare typed statements, which were not always verbatim transcripts of the recordings and were not generally signed by the witnesses. The Inquiry received all the original tape recordings from Kathleen Keville and arranged for them to be fully transcribed. In this report, when referring to what a witness said as recorded by Kathleen Keville, we usually describe this as the witness’s “Keville interview”.

Keville tapes

See Keville interviews.

Knights of Malta

The Order of Malta Ambulance Corps is an ambulance and first aid organisation administered by the Irish Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. Several members of the Derry Unit of the Ambulance Corps were on duty at the march on 30th January 1972 and provided first aid services. They were readily identifiable in that they wore either the dress uniform of the Ambulance Corps (a grey coat and trousers with cap) or its medical uniform (a white coat). They were often, although inaccurately, described by witnesses as Knights of Malta.

This was the technical designation for the 7.62mm self-loading rifle. See SLR.

This was the technical designation for the bolt-action .303in rifle converted to take 7.62mm ammunition. See Sniper rifle.

This was the technical designation for standard issue 7.62mm NATO ball ammunition, which was used in the L1A1 SLR and the L42A1 sniper rifle.

The M1 carbine is a semi-automatic or self-loading weapon that, in its standard form, comes with a fixed wooden stock. It was calibrated for a .30in cartridge. The weapon is sometimes described as being of medium velocity although some witnesses to the Inquiry referred to it as a high velocity weapon. There is evidence before the Inquiry to suggest that in Londonderry on 30th January 1972 the Official IRA possessed at least one M1 carbine and the Provisional IRA at least two. The weapon was not issued to any soldiers.

The following photographs show an M1 carbine.

Mahon interviews

Paul Mahon is a former member of Liverpool City Council who completed an academic dissertation on the events of Bloody Sunday in 1997. Thereafter he undertook further substantial research into the subject with the benefit of funding from an English businessman. In the course of this research he conducted a large number of recorded interviews of witnesses. He also co-operated with some of the solicitors acting for the families of the deceased and for the wounded, and for a time was employed by those acting for two of the wounded, Michael Bradley and Michael Bridge. The great majority of those interviewed by Paul Mahon were civilian witnesses.

Paul Mahon provided the Inquiry with both audiotapes and video recordings. The Inquiry arranged for the transcription of these recorded interviews.

McGovern interviews

Jimmy (James) McGovern was the scriptwriter of Sunday, a dramatisation of some of the events of Bloody Sunday. The programme was co-produced by Gaslight Productions Ltd and Box TV Ltd.

It was broadcast on Channel 4 on 28th January 2002 to mark the 30th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In preparing for the programme, Jimmy McGovern and Stephen Gargan of Gaslight Productions Ltd conducted a series of interviews with civilian witnesses to the events of Bloody Sunday. These interviews were recorded on audio tape. We were supplied with transcripts of these interviews together with the recordings. In addition, members of the production team conducted a number of interviews with civilians and former soldiers, which were not recorded. The notes of these interviews, where available, were also provided to the Inquiry.

Mura Place

The fourth, fifth and sixth floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Mura Place.

Nail bombs

These were improvised explosive devices containing nails as shrapnel. In Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, the use of nail bombs was associated particularly with the Provisional IRA. The typical nail bomb used at that time was a small cylindrical anti-personnel device, designed to be thrown by hand, which contained a fuse, a high explosive charge and a quantity of nails. These were sometimes inserted into an empty food or drink can, but by 1972 it had become more common for the components to be bound together with adhesive tape than for a can to be used.

The photograph below, which was obtained from the Regimental Headquarters of the Parachute Regiment, shows an unexploded nail bomb recovered during or after a riot in 1971.

NCCL

National Council for Civil Liberties. NCCL, now known as Liberty, is a civil rights organisation based in London, to which NICRA was affiliated.

NICRA

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. NICRA was founded in 1967. The organisation campaigned for civil rights and social justice.

NICRA statements

Over a period that began on the evening of Bloody Sunday and continued for several days thereafter, statements were taken from a large number of civilian witnesses in a process co-ordinated by NCCL and NICRA. The statement takers were volunteers. They interviewed witnesses and prepared handwritten statements, which were usually signed by both the witness and the statement taker. Typed versions of these statements were then produced. The statements gathered by NICRA and NCCL also included unsigned typed statements prepared from the recordings made by Kathleen Keville (see Keville interviews). We have referred to the statements collected by NICRA and NCCL either as “NICRA statements”, the term by which they were generally known during the Inquiry, or, where appropriate, as “Keville interviews”.

North tape

Susan North was the assistant of Fulvio Grimaldi, an Italian photographer and journalist. She and Fulvio Grimaldi both took part in the civil rights march on Bloody Sunday. Susan North carried a tape recorder, which she used to record some of the events that occurred on that day. The Inquiry obtained a copy of her recording and arranged for it to be transcribed. The tape is sometimes referred to as the “Grimaldi tape”.

Observer galley proofs

The Observer newspaper had intended to publish a substantial article about Bloody Sunday in its edition of 6th February 1972, but did not proceed because of a concern that publication might be regarded as contempt of the Widgery Inquiry. However, the article existed in draft form and the galley proofs have survived.

OIRA

Official Irish Republican Army. See IRA.

OP

Observation Post.

Petrol bombs

These were improvised devices consisting of a bottle filled with petrol (gasoline), with a fuse of cloth or similar material, which was lit before the bottle was thrown.

Pig

See APC.

PIRA

Provisional Irish Republican Army. See IRA.

Porter tapes

James Porter was an electrical engineer and radio enthusiast who had been recording Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) radio communications in Londonderry since 1969. He provided the Inquiry with copies of a number of his tapes, including his recordings of transmissions on the Brigade net and on the RUC radio network on Bloody Sunday. The Inquiry made transcripts of these recordings.

Praxis interviews

Praxis Films Ltd, a film and television production company, made a documentary entitled Bloody Sunday which was broadcast as part of Channel 4’s Secret History series on 5th December 1991, a few weeks before the 20th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In the course of researching and making the programme, the producer John Goddard, the director and scriptwriter Tony Stark and the researcher Neil Davies interviewed a large number of civilian and military witnesses. Neil Davies is a former member of Support Company, 1 PARA, although he left the Army in 1969 and never served in Northern Ireland. It appears that not all of the research material for the programme survived, but the Inquiry obtained notes and transcripts of many of the interviews.

Pringle interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

RMP

Royal Military Police. The RMP are the Army’s specialists in investigations and policing and are responsible for policing the United Kingdom military community worldwide.

RMP maps

The RMP statements taken from each of the soldiers who fired live ammunition on Bloody Sunday were accompanied by a map marked in typescript to show the position of that soldier at the time he fired and the location of his target or targets. In some cases the RMP statements of soldiers who did not fire live ammunition were also accompanied by maps marked to show relevant locations. It appears that the RMP maps were prepared after the statements were taken, from the information given in the statements. It also appears that the RMP maps were neither checked nor signed by the soldiers making the statements.

RMP statements

It was normal procedure in 1972 for the RMP to conduct an investigation following an incident in which a soldier had fired live ammunition. Beginning on the evening of Bloody Sunday, statements were taken from those soldiers who admitted firing shots. In addition a number of statements were taken from other soldiers. These statements were taken predominantly by members of the Special Investigation Branch (SIB) of the RMP. The statements were handwritten on standard statement forms from which typed versions were then made.

Rodgers film

Michael Rodgers, an amateur cameraman, took part in the march on 30th January 1972 and used a cine camera to film some of the events that occurred on that day. His film footage was later transferred to a video recording, a copy of which was provided to the Inquiry.

Rubber bullet gun

See Baton gun.

RUC

Royal Ulster Constabulary. This was the civilian police force in Northern Ireland. The present police force is called the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

RUC gun

See Baton gun.

RUC statements

On and after Bloody Sunday, RUC officers took statements from a number of witnesses, including several of those who had been wounded. RUC officers who had been on duty in Londonderry also submitted reports to their superiors of what they had themselves seen and heard.

Saracen

See APC.

Sayle Report

Harold Evans was editor of the Sunday Times newspaper in January 1972. He informed this Inquiry that immediately after the events of Bloody Sunday he sent general reporters Murray Sayle and Derek Humphry, along with Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times Insight Team, to Londonderry. At some stage that week Murray Sayle, Derek Humphry and (he thought) Peter Pringle telephoned in their findings. Harold Evans told us that these findings ran into two difficulties. In the first place, those in charge of the Insight Team were concerned as to whether the sources had been exposed to close enough scrutiny. They were strongly against publishing what came to be known as the Sayle Report as it stood. The second consideration in Harold Evans’ mind regarding the Sayle Report was that Lord Widgery, the Lord Chief Justice, had made it clear that he would regard publication during his inquiry as a serious handicap, so much so that he would regard such publication as a contempt of court. These two considerations Ied Harold Evans to decide not to publish the article, but to conduct another investigation, using the Sunday Times Insight Team, led by John Barry. The Sunday Times provided this Inquiry with a copy of the Sayle Report. See also Sunday Times interviews.

SLR

The L1A1 self-loading rifle (SLR) was the standard issue high velocity rifle in general infantry service in the Army in 1972. It was used with 7.62mm L2A2 ammunition. On Bloody Sunday the majority of soldiers carried SLRs.

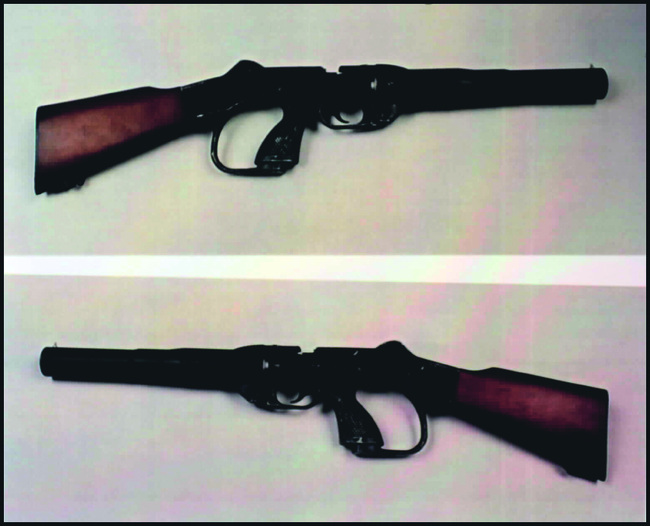

The following photographs show an SLR.

Sub-machine gun. See Sterling sub-machine gun and Thompson sub-machine gun.

Sniper rifle

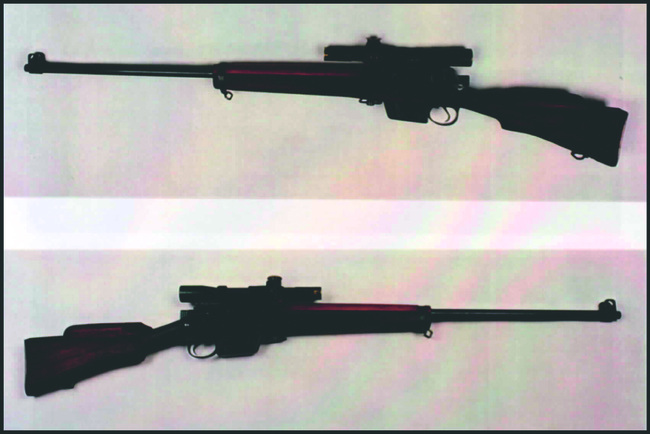

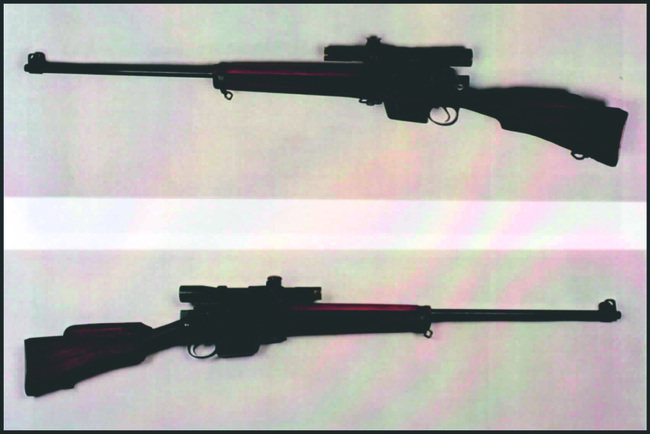

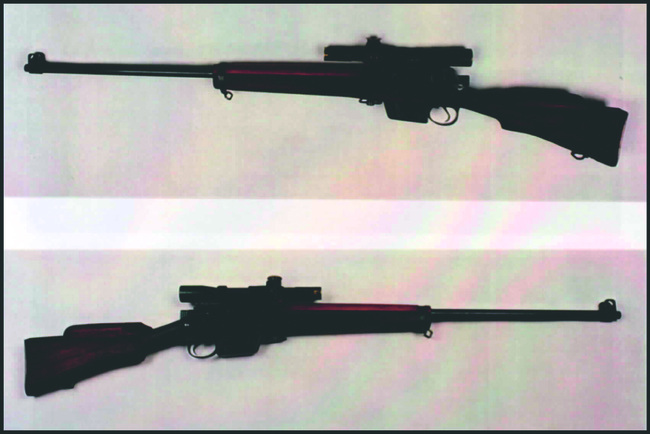

The L42A1 sniper rifle was a bolt action .303in rifle converted to take 7.62mm L2A2 ammunition. On Bloody Sunday a small number of soldiers carried sniper rifles.

The photographs below show a sniper rifle.

Sterling sub-machine gun

The Sterling was a low velocity 9mm SMG. A small number of soldiers carried Sterling SMGs on Bloody Sunday. The Derry Brigade of the Official IRA may also have possessed a Sterling SMG.

The following photographs show a Sterling SMG.

Sunday Times interviews

In the week following Bloody Sunday, journalists from the Insight Team of the Sunday Times newspaper began a major investigation of the events of that day. The investigation continued while the Widgery Inquiry was sitting, and culminated in the publication of a substantial article in the Sunday Times on 23rd April 1972, four days after the report of the Widgery Inquiry had been presented to Parliament. The Insight editor, John Barry, led the investigation. He and two other Insight journalists, Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle, interviewed a large number of witnesses in Londonderry, including members of the Official IRA and Provisional IRA. The Sunday Times provided this Inquiry with such material from the Insight investigation, including notes and transcripts of the interviews conducted by John Barry and his colleagues, as has survived in the newspaper’s archive.

Taylor interviews

Peter Taylor is a broadcaster and author who has made many documentaries and written several books about the conflict in Northern Ireland since his first visit there on Bloody Sunday. He conducted on-the-record filmed interviews of a number of civilian and military witnesses in the course of making a documentary entitled Remember Bloody Sunday, which was broadcast by the BBC on 28th January 1992 to mark the 20th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. Transcripts of these interviews were supplied to the Inquiry.

Thompson sub-machine gun

The Thompson SMG is a low velocity automatic weapon also capable of firing single shots. There is evidence before the Inquiry to suggest that on 30th January 1972 the Official IRA in Londonderry possessed at least one Thompson SMG and the Provisional IRA at least two. The weapon was not issued to any soldiers.

The photograph below shows a Thompson SMG.

Trajectory photographs

At the request of the Widgery Inquiry, a series of aerial photographs of the relevant area of Londonderry was created in February 1972 to illustrate the trajectories of the shots that soldiers claimed to have fired on Bloody Sunday. Each photograph was marked to show the positions of the soldier and of his target, as the soldier had described them; the line of fire between those positions; and in some cases the number of shots that the soldier claimed to have fired. One or more of these photographs was created for each soldier of 1 PARA who acknowledged that he had fired his rifle on Bloody Sunday.

Ulsternet

The Ulsternet was a radio network used by the Army throughout Northern Ireland at the time of Bloody Sunday. It provided the main radio link between the headquarters of each brigade and the units under its command. Transmissions on the Ulsternet could be monitored at HQNI but the system was not used as the primary means of communication between HQNI and 8th Infantry Brigade headquarters. The Ulsternet was in use on Bloody Sunday as the Brigade net, providing communications between 8th Infantry Brigade Headquarters at Ebrington Barracks and the units under its command, including 1 PARA.

Virtual reality model

This was a computer simulation of the Bogside as it was in 1972, which was developed for use by this Inquiry in order to assist witnesses in giving their accounts of what they had heard and seen on Bloody Sunday. This was of particular assistance because the area has changed since 1972.

Widgery Inquiry

Following resolutions passed on 1st February 1972 in both Houses of Parliament at Westminster and in both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Widgery, was appointed to conduct an Inquiry under the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921 into “the events on Sunday, 30th January which led to loss of life in connection with the procession in Londonderry on that day”. Lord Widgery was the sole member of the Tribunal. He sat at the County Hall, Coleraine, for a preliminary hearing on 14th February 1972 and for the main hearings from 21st February 1972 to 14th March 1972. He heard closing speeches on 16th, 17th and 20th March 1972 at the Royal Courts of Justice in London. The Report of the Widgery Inquiry was presented to Parliament on 19th April 1972.

Widgery statements

The Deputy Treasury Solicitor, Basil Hall (later Sir Basil Hall), was appointed as the Solicitor to the Widgery Inquiry. For the purposes of that Inquiry, he and his assistants interviewed a large number of witnesses and prepared written statements from the interviews. A smaller number of witnesses submitted their own statements to the Widgery Inquiry, either directly or through solicitors. This Inquiry obtained copies of all the Widgery Inquiry statements.

Widgery transcripts

Transcripts are available of all the oral hearings of the Widgery Inquiry. During those hearings, witnesses were often asked to illustrate their evidence by reference to a model of the Bogside area which had been made for that purpose. It is occasionally not possible to follow the explanation recorded in the transcripts without knowing to which part of the model the witness was pointing.

This Inquiry tried unsuccessfully to locate the model used at the Widgery Inquiry. Although the original model appears not to have survived, it can be seen in the following photograph.

Widgery Tribunal

See Widgery Inquiry.

Yellow Card

Every soldier serving in Northern Ireland was issued with a copy of a card, entitled “Instructions by the Director of Operations for Opening Fire in Northern Ireland”, which defined the circumstances in which he was permitted to open fire. This card was known as the Yellow Card. All soldiers were expected to be familiar with, and to obey, the rules contained in it. The Yellow Card was first issued in September 1969 and was revised periodically thereafter. The fourth edition of the Yellow Card, issued in November 1971, was current on 30th January 1972.

List of Army ranks

The list below shows, in order of seniority, the Army ranks to which we refer in this report, together with the abbreviations sometimes used for them. Lieutenant Generals and Major Generals are both commonly referred to and addressed simply as General, and similarly Lieutenant Colonels as Colonel.

Officers

Field Marshal

FM

General

Gen

Lieutenant General

Lt Gen

Major General

Maj Gen

Brigadier

Brig

Colonel

Col

Lieutenant Colonel

Lt Col

Major

Maj

Captain

Capt

Lieutenant

Lt

Second Lieutenant

2 Lt

Warrant Officers

Warrant Officer Class I

WOI

Warrant Officer Class II

WOII

Senior non-commissioned officers

Equivalent ranks

Colour Sergeant

C/Sgt

Staff Sergeant

S/Sgt

Sergeant

Sgt

Junior non-commissioned officers

Equivalent ranks

Corporal

Cpl

Lance Sergeant

L/Sgt

Bombardier

Bdr

Lance Corporal

L/Cpl

Lance Bombardier

L/Bdr

Soldiers

Equivalent ranks

Private

Pte

Guardsman

Gdsm

Gunner

Gnr

Rifleman

Rfn

In this glossary we provide brief explanations of some of the abbreviations and terminology used in the report, or which appear in some of the documents and other evidence to which we refer. Where necessary, in the report itself we provide further details of, in particular, some of the sources of evidence and the issues to which they gave rise. At the end of the glossary we set out a list showing the hierarchy of Army ranks and the abbreviations sometimes used for them. Cross-references within the glossary to other entries in the glossary appear in italics.

Acid bombs

These were bottles filled with acid or another corrosive substance, used as anti-personnel weapons.

Actuality footage

We have used this expression to refer to film footage taken while the events of Bloody Sunday were in progress. The actuality footage available to the Inquiry includes material filmed by two cameramen from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), two from Independent Television News (ITN), one from the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) and one from Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), as well as a film taken from an Army helicopter. There is also a small quantity of actuality footage taken by amateur cameramen, including William McKinney, who was shot dead on Bloody Sunday. Some of the film footage was edited for broadcasting purposes, with the result that the surviving material is not complete and does not necessarily show events in chronological order.

Aggro Corner

This was a slang name, used mainly by the Army, which referred to the junction of William Street, Rossville Street and Little James Street, where trouble had often occurred in the past.

Anti-riot gun

See Baton gun.

APC

Armoured Personnel Carrier. The Humber armoured car was employed routinely as an APC by the Army in Northern Ireland. Several of these vehicles were used on Bloody Sunday. They were often called “Pigs”, mainly by soldiers, either on account of their appearance or because they were awkward to drive and uncomfortable to sit in. They were also frequently described, usually by civilians, as “Saracens”. However, that term was applied inaccurately, since a Saracen was another type of military vehicle, which was not used on Bloody Sunday.

The following photograph, taken by Robert White on Bloody Sunday, shows a Humber APC.

The following photograph, taken from David Barzilay, The British Army in Ulster (Belfast: Century Books, 1978 reprint), shows a Saracen.

Army units

8 Inf Bde

8th Infantry Brigade.

39 Inf Bde

39th Infantry Brigade.

1 CG

1st Battalion, The Coldstream Guards.

1 PARA

1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment.

1 R ANGLIAN

1st Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment.

2 RGJ

2nd Battalion, The Royal Green Jackets.

22 Lt AD Regt

22nd Light Air Defence Regiment, Royal Artillery.

Arrest report forms

When a civilian who had been arrested by a soldier came into the custody of the Royal Military Police (RMP), details of the arrest, including the names of the soldier, the arrested civilian and any witnesses, and the nature of the offence alleged to have been committed, were recorded on what was known as an arrest report form. The form also included space in which to record the date, time and place at which the arrested person was handed over to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and for the RUC to record, where appropriate, the date and time at which the arrested person was charged and whether he or she was kept in custody or released on bail.

Barry interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

Baton gun

A baton gun was a weapon used to fire baton rounds, otherwise known as rubber bullets, for riot control purposes. On Bloody Sunday many of the soldiers were equipped with baton guns. The baton gun was also known by a variety of other names, including “anti-riot gun”, “RUC gun”, “rubber bullet gun” and “Greener gun”.

The following photographs show a baton gun.

BID 150

In 1972 the Army in Northern Ireland had access to a secure radio system. Secure communications between a brigade and a battalion under its command could be achieved using an adapted military radio together with a piece of encryption equipment called a BID 150. In this Inquiry the term “BID 150” was often used to refer to the radio and the encryption device together. Whether a BID 150 link was in use between Brigade HQ and the Tactical Headquarters of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday was a matter of dispute, which we consider in the course of the report.

Blast bombs

Blast bombs were improvised devices that consisted of a detonator and explosive material. They were described by some witnesses as being crude anti-personnel devices and like large fireworks or nail bombs but without the nails. We also heard evidence that they could be made with a larger quantity of explosives in order to be used to damage buildings.

Bloody Sunday Inquiry statements

In the course of this Inquiry, written statements were obtained from a large number of witnesses, including civilians, former and serving soldiers, priests, journalists, civil servants, politicians and former members of the IRA. The vast majority of these statements (sometimes called “BSI statements”) were taken by the solicitors Eversheds, who were retained by this Inquiry for this purpose. For this reason some are also sometimes referred to as “Eversheds statements”. The Solicitor to the Inquiry and his assistants also took a number of written statements, and a few were submitted by witnesses or their solicitors.

Brigade HQ

The headquarters of 8th Infantry Brigade, located at Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry.

Brigade net

This was the radio network used to provide communications between Brigade HQ and the headquarters of the battalions and other units under its command. Separate radio networks were used for communications between the headquarters of each battalion and its constituent companies. See also Ulsternet.

Capper tapes

David Capper was a BBC Radio reporter who covered the march on Bloody Sunday. He carried a reel-to-reel tape recorder on which he recorded his commentary on the march. Other voices and sounds are also audible on the recording. The Inquiry obtained a copy of the recording and arranged for a transcript to be made.

CS gas

This is a type of tear gas, which could be fired in grenades or cartridges as a riot control agent.

DIFS

The Department of Industrial and Forensic Science. This department, which formed part of the Ministry of Commerce of the Government of Northern Ireland, was responsible for the forensic tests carried out shortly after Bloody Sunday on hand swabs and clothing obtained from those who had been killed. It was also responsible for matching two bullets, recovered from the bodies of Gerald Donaghey and Michael Kelly, to rifles fired by soldiers on that day.

Donagh Place

The seventh, eighth and ninth floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Donagh Place.

Embassy Ballroom

The Embassy Ballroom was located on the west side of Strand Road, close to the northern corner of Waterloo Place. In January 1972 the Army occupied the top floor of the building. Two Observation Posts (OPs) were sited on the roof. OP Echo gave views of William Street, Little James Street, Chamberlain Street, the waste ground north of the Rossville Flats, and the Rossville Flats themselves, including the roofs. OP Foxtrot overlooked Strand Road and Waterloo Place. On Bloody Sunday members of 11 Battery 22 Lt AD Regt manned both these OPs.

Eversheds statements

See Bloody Sunday Inquiry statements.

Ferguson and Thomson interviews

Lena Ferguson and Alexander Thomson were ITN journalists who interviewed a number of former soldiers for the purposes of a Channel 4 News investigation of Bloody Sunday, which resulted in a series of broadcasts transmitted in 1997 and 1998.

Ferret scout car

The Ferret was a lightly armoured scout car which had a two-man crew. On Bloody Sunday, Support Company, 1 PARA used one Ferret scout car, on which a Browning machine gun was mounted. This weapon was not used on Bloody Sunday.

The photograph below, taken by Colman Doyle on Bloody Sunday, shows the Ferret scout car used on that day.

Garvan Place

The first, second and third floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Garvan Place.

Gin Palace

The vehicle in which the tactical headquarters of 1 PARA was located was colloquially known as the Gin Palace.

Greener gun

See Baton gun.

Grimaldi tape

See North tape.

HQNI

Headquarters of the Army in Northern Ireland, located in Lisburn, County Antrim.

Humber armoured car

See APC.

IRA

Irish Republican Army. By 1972 this had split into two separate organisations, the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA. In many cases witnesses and documents referred simply to the IRA, without differentiating between these two organisations.

Jacobson interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

Keville interviews

Kathleen Keville was in Londonderry in January 1972 as a researcher for a film crew making a documentary about Northern Ireland. She had met members of the local civil rights organisation on a previous visit to the city. She took part in the march on 30th January 1972. On the evening of that day and into the next, she recorded the accounts of a number of civilian witnesses on audio tape. Many of these recordings were used to prepare typed statements, which were not always verbatim transcripts of the recordings and were not generally signed by the witnesses. The Inquiry received all the original tape recordings from Kathleen Keville and arranged for them to be fully transcribed. In this report, when referring to what a witness said as recorded by Kathleen Keville, we usually describe this as the witness’s “Keville interview”.

Keville tapes

See Keville interviews.

Knights of Malta

The Order of Malta Ambulance Corps is an ambulance and first aid organisation administered by the Irish Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. Several members of the Derry Unit of the Ambulance Corps were on duty at the march on 30th January 1972 and provided first aid services. They were readily identifiable in that they wore either the dress uniform of the Ambulance Corps (a grey coat and trousers with cap) or its medical uniform (a white coat). They were often, although inaccurately, described by witnesses as Knights of Malta.

This was the technical designation for the 7.62mm self-loading rifle. See SLR.

This was the technical designation for the bolt-action .303in rifle converted to take 7.62mm ammunition. See Sniper rifle.

This was the technical designation for standard issue 7.62mm NATO ball ammunition, which was used in the L1A1 SLR and the L42A1 sniper rifle.

The M1 carbine is a semi-automatic or self-loading weapon that, in its standard form, comes with a fixed wooden stock. It was calibrated for a .30in cartridge. The weapon is sometimes described as being of medium velocity although some witnesses to the Inquiry referred to it as a high velocity weapon. There is evidence before the Inquiry to suggest that in Londonderry on 30th January 1972 the Official IRA possessed at least one M1 carbine and the Provisional IRA at least two. The weapon was not issued to any soldiers.

The following photographs show an M1 carbine.

Mahon interviews

Paul Mahon is a former member of Liverpool City Council who completed an academic dissertation on the events of Bloody Sunday in 1997. Thereafter he undertook further substantial research into the subject with the benefit of funding from an English businessman. In the course of this research he conducted a large number of recorded interviews of witnesses. He also co-operated with some of the solicitors acting for the families of the deceased and for the wounded, and for a time was employed by those acting for two of the wounded, Michael Bradley and Michael Bridge. The great majority of those interviewed by Paul Mahon were civilian witnesses.

Paul Mahon provided the Inquiry with both audiotapes and video recordings. The Inquiry arranged for the transcription of these recorded interviews.

McGovern interviews

Jimmy (James) McGovern was the scriptwriter of Sunday, a dramatisation of some of the events of Bloody Sunday. The programme was co-produced by Gaslight Productions Ltd and Box TV Ltd.

It was broadcast on Channel 4 on 28th January 2002 to mark the 30th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In preparing for the programme, Jimmy McGovern and Stephen Gargan of Gaslight Productions Ltd conducted a series of interviews with civilian witnesses to the events of Bloody Sunday. These interviews were recorded on audio tape. We were supplied with transcripts of these interviews together with the recordings. In addition, members of the production team conducted a number of interviews with civilians and former soldiers, which were not recorded. The notes of these interviews, where available, were also provided to the Inquiry.

Mura Place

The fourth, fifth and sixth floors of the Rossville Flats were known as Mura Place.

Nail bombs

These were improvised explosive devices containing nails as shrapnel. In Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, the use of nail bombs was associated particularly with the Provisional IRA. The typical nail bomb used at that time was a small cylindrical anti-personnel device, designed to be thrown by hand, which contained a fuse, a high explosive charge and a quantity of nails. These were sometimes inserted into an empty food or drink can, but by 1972 it had become more common for the components to be bound together with adhesive tape than for a can to be used.

The photograph below, which was obtained from the Regimental Headquarters of the Parachute Regiment, shows an unexploded nail bomb recovered during or after a riot in 1971.

NCCL

National Council for Civil Liberties. NCCL, now known as Liberty, is a civil rights organisation based in London, to which NICRA was affiliated.

NICRA

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. NICRA was founded in 1967. The organisation campaigned for civil rights and social justice.

NICRA statements

Over a period that began on the evening of Bloody Sunday and continued for several days thereafter, statements were taken from a large number of civilian witnesses in a process co-ordinated by NCCL and NICRA. The statement takers were volunteers. They interviewed witnesses and prepared handwritten statements, which were usually signed by both the witness and the statement taker. Typed versions of these statements were then produced. The statements gathered by NICRA and NCCL also included unsigned typed statements prepared from the recordings made by Kathleen Keville (see Keville interviews). We have referred to the statements collected by NICRA and NCCL either as “NICRA statements”, the term by which they were generally known during the Inquiry, or, where appropriate, as “Keville interviews”.

North tape

Susan North was the assistant of Fulvio Grimaldi, an Italian photographer and journalist. She and Fulvio Grimaldi both took part in the civil rights march on Bloody Sunday. Susan North carried a tape recorder, which she used to record some of the events that occurred on that day. The Inquiry obtained a copy of her recording and arranged for it to be transcribed. The tape is sometimes referred to as the “Grimaldi tape”.

Observer galley proofs

The Observer newspaper had intended to publish a substantial article about Bloody Sunday in its edition of 6th February 1972, but did not proceed because of a concern that publication might be regarded as contempt of the Widgery Inquiry. However, the article existed in draft form and the galley proofs have survived.

OIRA

Official Irish Republican Army. See IRA.

OP

Observation Post.

Petrol bombs

These were improvised devices consisting of a bottle filled with petrol (gasoline), with a fuse of cloth or similar material, which was lit before the bottle was thrown.

Pig

See APC.

PIRA

Provisional Irish Republican Army. See IRA.

Porter tapes

James Porter was an electrical engineer and radio enthusiast who had been recording Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) radio communications in Londonderry since 1969. He provided the Inquiry with copies of a number of his tapes, including his recordings of transmissions on the Brigade net and on the RUC radio network on Bloody Sunday. The Inquiry made transcripts of these recordings.

Praxis interviews

Praxis Films Ltd, a film and television production company, made a documentary entitled Bloody Sunday which was broadcast as part of Channel 4’s Secret History series on 5th December 1991, a few weeks before the 20th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In the course of researching and making the programme, the producer John Goddard, the director and scriptwriter Tony Stark and the researcher Neil Davies interviewed a large number of civilian and military witnesses. Neil Davies is a former member of Support Company, 1 PARA, although he left the Army in 1969 and never served in Northern Ireland. It appears that not all of the research material for the programme survived, but the Inquiry obtained notes and transcripts of many of the interviews.

Pringle interviews

See Sunday Times interviews.

RMP

Royal Military Police. The RMP are the Army’s specialists in investigations and policing and are responsible for policing the United Kingdom military community worldwide.

RMP maps

The RMP statements taken from each of the soldiers who fired live ammunition on Bloody Sunday were accompanied by a map marked in typescript to show the position of that soldier at the time he fired and the location of his target or targets. In some cases the RMP statements of soldiers who did not fire live ammunition were also accompanied by maps marked to show relevant locations. It appears that the RMP maps were prepared after the statements were taken, from the information given in the statements. It also appears that the RMP maps were neither checked nor signed by the soldiers making the statements.

RMP statements

It was normal procedure in 1972 for the RMP to conduct an investigation following an incident in which a soldier had fired live ammunition. Beginning on the evening of Bloody Sunday, statements were taken from those soldiers who admitted firing shots. In addition a number of statements were taken from other soldiers. These statements were taken predominantly by members of the Special Investigation Branch (SIB) of the RMP. The statements were handwritten on standard statement forms from which typed versions were then made.

Rodgers film

Michael Rodgers, an amateur cameraman, took part in the march on 30th January 1972 and used a cine camera to film some of the events that occurred on that day. His film footage was later transferred to a video recording, a copy of which was provided to the Inquiry.

Rubber bullet gun

See Baton gun.

RUC

Royal Ulster Constabulary. This was the civilian police force in Northern Ireland. The present police force is called the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

RUC gun

See Baton gun.

RUC statements

On and after Bloody Sunday, RUC officers took statements from a number of witnesses, including several of those who had been wounded. RUC officers who had been on duty in Londonderry also submitted reports to their superiors of what they had themselves seen and heard.

Saracen

See APC.

Sayle Report

Harold Evans was editor of the Sunday Times newspaper in January 1972. He informed this Inquiry that immediately after the events of Bloody Sunday he sent general reporters Murray Sayle and Derek Humphry, along with Peter Pringle of the Sunday Times Insight Team, to Londonderry. At some stage that week Murray Sayle, Derek Humphry and (he thought) Peter Pringle telephoned in their findings. Harold Evans told us that these findings ran into two difficulties. In the first place, those in charge of the Insight Team were concerned as to whether the sources had been exposed to close enough scrutiny. They were strongly against publishing what came to be known as the Sayle Report as it stood. The second consideration in Harold Evans’ mind regarding the Sayle Report was that Lord Widgery, the Lord Chief Justice, had made it clear that he would regard publication during his inquiry as a serious handicap, so much so that he would regard such publication as a contempt of court. These two considerations Ied Harold Evans to decide not to publish the article, but to conduct another investigation, using the Sunday Times Insight Team, led by John Barry. The Sunday Times provided this Inquiry with a copy of the Sayle Report. See also Sunday Times interviews.

SLR

The L1A1 self-loading rifle (SLR) was the standard issue high velocity rifle in general infantry service in the Army in 1972. It was used with 7.62mm L2A2 ammunition. On Bloody Sunday the majority of soldiers carried SLRs.

The following photographs show an SLR.

Sub-machine gun. See Sterling sub-machine gun and Thompson sub-machine gun.

Sniper rifle

The L42A1 sniper rifle was a bolt action .303in rifle converted to take 7.62mm L2A2 ammunition. On Bloody Sunday a small number of soldiers carried sniper rifles.

The photographs below show a sniper rifle.

Sterling sub-machine gun

The Sterling was a low velocity 9mm SMG. A small number of soldiers carried Sterling SMGs on Bloody Sunday. The Derry Brigade of the Official IRA may also have possessed a Sterling SMG.

The following photographs show a Sterling SMG.

Sunday Times interviews

In the week following Bloody Sunday, journalists from the Insight Team of the Sunday Times newspaper began a major investigation of the events of that day. The investigation continued while the Widgery Inquiry was sitting, and culminated in the publication of a substantial article in the Sunday Times on 23rd April 1972, four days after the report of the Widgery Inquiry had been presented to Parliament. The Insight editor, John Barry, led the investigation. He and two other Insight journalists, Philip Jacobson and Peter Pringle, interviewed a large number of witnesses in Londonderry, including members of the Official IRA and Provisional IRA. The Sunday Times provided this Inquiry with such material from the Insight investigation, including notes and transcripts of the interviews conducted by John Barry and his colleagues, as has survived in the newspaper’s archive.

Taylor interviews

Peter Taylor is a broadcaster and author who has made many documentaries and written several books about the conflict in Northern Ireland since his first visit there on Bloody Sunday. He conducted on-the-record filmed interviews of a number of civilian and military witnesses in the course of making a documentary entitled Remember Bloody Sunday, which was broadcast by the BBC on 28th January 1992 to mark the 20th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. Transcripts of these interviews were supplied to the Inquiry.

Thompson sub-machine gun

The Thompson SMG is a low velocity automatic weapon also capable of firing single shots. There is evidence before the Inquiry to suggest that on 30th January 1972 the Official IRA in Londonderry possessed at least one Thompson SMG and the Provisional IRA at least two. The weapon was not issued to any soldiers.

The photograph below shows a Thompson SMG.

Trajectory photographs

At the request of the Widgery Inquiry, a series of aerial photographs of the relevant area of Londonderry was created in February 1972 to illustrate the trajectories of the shots that soldiers claimed to have fired on Bloody Sunday. Each photograph was marked to show the positions of the soldier and of his target, as the soldier had described them; the line of fire between those positions; and in some cases the number of shots that the soldier claimed to have fired. One or more of these photographs was created for each soldier of 1 PARA who acknowledged that he had fired his rifle on Bloody Sunday.

Ulsternet

The Ulsternet was a radio network used by the Army throughout Northern Ireland at the time of Bloody Sunday. It provided the main radio link between the headquarters of each brigade and the units under its command. Transmissions on the Ulsternet could be monitored at HQNI but the system was not used as the primary means of communication between HQNI and 8th Infantry Brigade headquarters. The Ulsternet was in use on Bloody Sunday as the Brigade net, providing communications between 8th Infantry Brigade Headquarters at Ebrington Barracks and the units under its command, including 1 PARA.

Virtual reality model

This was a computer simulation of the Bogside as it was in 1972, which was developed for use by this Inquiry in order to assist witnesses in giving their accounts of what they had heard and seen on Bloody Sunday. This was of particular assistance because the area has changed since 1972.

Widgery Inquiry

Following resolutions passed on 1st February 1972 in both Houses of Parliament at Westminster and in both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Widgery, was appointed to conduct an Inquiry under the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921 into “the events on Sunday, 30th January which led to loss of life in connection with the procession in Londonderry on that day”. Lord Widgery was the sole member of the Tribunal. He sat at the County Hall, Coleraine, for a preliminary hearing on 14th February 1972 and for the main hearings from 21st February 1972 to 14th March 1972. He heard closing speeches on 16th, 17th and 20th March 1972 at the Royal Courts of Justice in London. The Report of the Widgery Inquiry was presented to Parliament on 19th April 1972.

Widgery statements

The Deputy Treasury Solicitor, Basil Hall (later Sir Basil Hall), was appointed as the Solicitor to the Widgery Inquiry. For the purposes of that Inquiry, he and his assistants interviewed a large number of witnesses and prepared written statements from the interviews. A smaller number of witnesses submitted their own statements to the Widgery Inquiry, either directly or through solicitors. This Inquiry obtained copies of all the Widgery Inquiry statements.

Widgery transcripts

Transcripts are available of all the oral hearings of the Widgery Inquiry. During those hearings, witnesses were often asked to illustrate their evidence by reference to a model of the Bogside area which had been made for that purpose. It is occasionally not possible to follow the explanation recorded in the transcripts without knowing to which part of the model the witness was pointing.

This Inquiry tried unsuccessfully to locate the model used at the Widgery Inquiry. Although the original model appears not to have survived, it can be seen in the following photograph.

Widgery Tribunal

See Widgery Inquiry.

Yellow Card

Every soldier serving in Northern Ireland was issued with a copy of a card, entitled “Instructions by the Director of Operations for Opening Fire in Northern Ireland”, which defined the circumstances in which he was permitted to open fire. This card was known as the Yellow Card. All soldiers were expected to be familiar with, and to obey, the rules contained in it. The Yellow Card was first issued in September 1969 and was revised periodically thereafter. The fourth edition of the Yellow Card, issued in November 1971, was current on 30th January 1972.

List of Army ranks

The list below shows, in order of seniority, the Army ranks to which we refer in this report, together with the abbreviations sometimes used for them. Lieutenant Generals and Major Generals are both commonly referred to and addressed simply as General, and similarly Lieutenant Colonels as Colonel.

Officers

Field Marshal

FM

General

Gen

Lieutenant General

Lt Gen

Major General

Maj Gen

Brigadier

Brig

Colonel

Col

Lieutenant Colonel

Lt Col

Major

Maj

Captain

Capt

Lieutenant

Lt

Second Lieutenant

2 Lt

Warrant Officers

Warrant Officer Class I

WOI

Warrant Officer Class II

WOII

Senior non-commissioned officers

Equivalent ranks

Colour Sergeant

C/Sgt

Staff Sergeant

S/Sgt

Sergeant

Sgt

Junior non-commissioned officers

Equivalent ranks

Corporal

Cpl

Lance Sergeant

L/Sgt

Bombardier

Bdr

Lance Corporal

L/Cpl

Lance Bombardier

L/Bdr

Soldiers

Equivalent ranks

Private

Pte

Guardsman

Gdsm

Gunner

Gnr

Rifleman

Rfn

Last edited by Antoinette on Tue 22 Jun - 21:50; edited 1 time in total

Guest- Guest

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

Re: Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry Volume 1

- Volume I - Chapter 1

Principal Conclusions and Overall Assessment

Chapter 1: Introduction

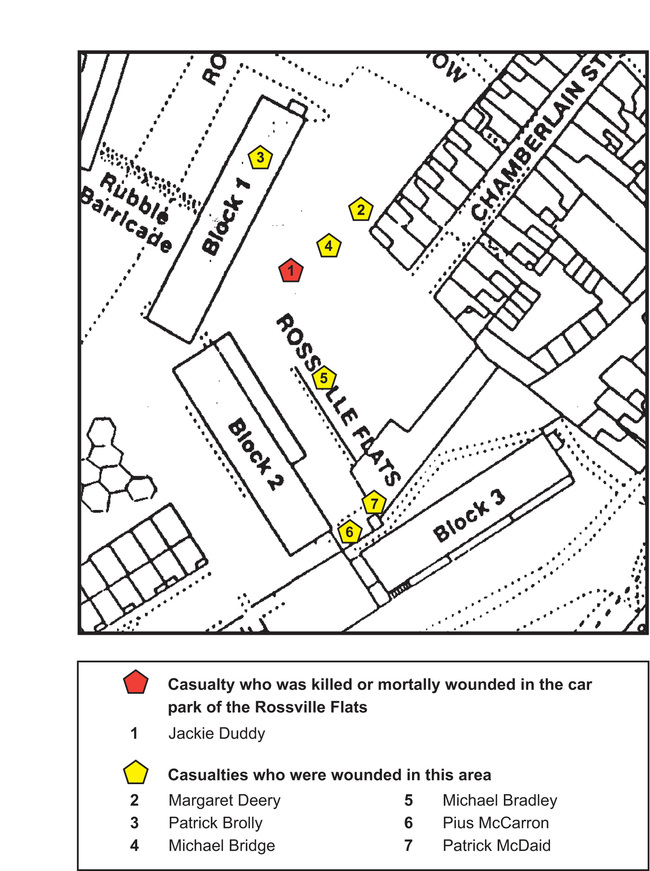

The object of the Inquiry was to examine the circumstances that led to loss of life in connection with the civil rights march in Londonderry on 30th January 1972. Thirteen civilians were killed by Army gunfire on the day. The day has become generally known as Bloody Sunday, which is why at the outset we called this Inquiry the Bloody Sunday Inquiry. In 1972 Lord Widgery, then the Lord Chief Justice of England, held an inquiry into these same events.

In these opening chapters of the report we provide an outline of events before and during 30th January 1972; and collect together for convenience the principal conclusions that we have reached on the events of that day. We also provide our overall assessment of what happened on Bloody Sunday. This outline, our principal conclusions and our overall assessment are based on a detailed examination and evaluation of the evidence, which can be found elsewhere in this report. These chapters should be read in conjunction with that detailed examination and evaluation, since there are many important details, including our reasons for the conclusions that we have reached, which we do not include here, in order to avoid undue repetition.

The Inquiry involved an examination of a complex set of events. In relation to the day itself, most of these events were fast moving and many occurred more or less simultaneously. In order to carry out a thorough investigation into events that have given rise to great controversy over many years, our examination necessarily involved the close consideration and analysis of a very large amount of evidence.

In addition to those killed, people were also injured by Army gunfire on Bloody Sunday. We took the view at the outset that it would be artificial in the extreme to ignore the injured, since those shooting incidents in the main took place in the same circumstances, at the same times and in the same places as those causing fatal injuries.

We found it necessary not to confine our investigations only to what happened on the day. Without examining what led up to Bloody Sunday, it would be impossible to reach a properly informed view of what happened, let alone of why it happened. An examination of what preceded Bloody Sunday was particularly important because there had been allegations that members of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland Governments, as well as the security forces, had so conducted themselves in the period up to Bloody Sunday that they bore a heavy responsibility for what happened on that day.

Many of the soldiers (including all those whose shots killed and injured people on Bloody Sunday) were granted anonymity at the Inquiry, after rulings by the Court of Appeal in London. We also granted other individuals anonymity, on the basis of the principles laid down by the Court of Appeal. Those granted anonymity were given ciphers in place of their names. We have preserved their anonymity in this report.